To this day one of the most important, yet least understood aspects of Bible prophecy is the history of Ezra, Nehemiah and their contemporary, the great Persian king “Artaxerxes”. Even less understood is how this history has shaped our understanding of Daniel 9, the prophecy of 70 Weeks, and our future eschatological expectations.

To this day one of the most important, yet least understood aspects of Bible prophecy is the history of Ezra, Nehemiah and their contemporary, the great Persian king “Artaxerxes”. Even less understood is how this history has shaped our understanding of Daniel 9, the prophecy of 70 Weeks, and our future eschatological expectations.

In the past few blog posts we have looked at three Persian decrees to “restore and build Jerusalem”. This week we will focus in on the forth and final Persian decree which scholars have long held as the decree “to restore and build Jerusalem”. This decree supposedly given by Artaxerxes Longimanus was popularized by the great Biblical scholar Sir Robert Anderson.

But what evidence did Anderson use to justify his position regarding Artaxerxes and the prophecy of 70 Weeks? Today we will answer these questions and frankly I think the answers may surprise so of you.

“Then I told them of the hand of my God which was good upon me; as also the king’s words [dabar] that he had spoken unto me. And they said, Let us rise up and build. So they strengthened their hands for this good work.” (Nehemiah 2:18)

Nearly thirteen years after Ezra went up to Jerusalem during the reign of Artaxerxes, we learn that Nehemiah, the cupbearer to that same Artaxerxes, received permission to travel to Jerusalem and rebuild the walls of the city, which were in disrepair. Here is the biblical account:

And it came to pass in the month Nisan, in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes the king, that wine was before him: and I took up the wine, and gave it unto the king. Now I had not been beforetime sad in his presence. (Nehemiah 2:1)

And I said unto the king, If it please the king, and if thy servant have found favour in thy sight, that thou wouldest send me unto Judah, unto the city of my fathers’ sepulchres, that I may build it. And the king said unto me, (the queen also sitting by him,) For how long shall thy journey be? and when wilt thou return?

So it pleased the king to send me; and I set him a time. Moreover I said unto the king, If it please the king, let letters be given me to the governors beyond the river, that they may convey me over till I come into Judah; and a letter unto Asaph the keeper of the king’s forest, that he may give me timber to make beams for the gates of the palace which appertained to the house, and for the wall of the city, and for the house that I shall enter into. And the king granted me, according to the good hand of my God upon me. (Nehemiah 2:5–8)

By far, the decree by this unnamed Persian Artaxerxes—once again presumed to be Longimanus, known to history as Artaxerxes I—is the most popular choice when scholars look for the commandment to restore and build Jerusalem prophesied by Daniel. As mentioned earlier, Sir Robert Anderson, the great Christian writer, popularized this theory in his influential book The Coming Prince. Anderson does indeed make an impressive case, but surprisingly, he fails to address the scriptural basis for his belief that Ezra and Nehemiah were contemporaries of Longimanus. Instead, Anderson, in one of the most far-reaching eschatological errors of the past two centuries, simply defers to the judgment of the great historian Rawlinson. I quote Rawlinson as found on p. 71 of Anderson’s The Coming Prince:

“Artaxerxes I reigned forty years, from 465 to 425. He is mentioned by Herodotus once (6. 98), by Thucydides frequently. Both writers were his contemporaries. There is every reason to believe that he was the king who sent Ezra and Nehemiah to Jerusalem, and sanctioned the restoration of the fortifications.”—RAWLINSON, Herodotus, vol. 4, p. 217.

Did you catch that? “There is every reason to believe” is the sum of Rawlinson’s and Anderson’s evidence for Ezra and Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era! Not a single reference to Ezra’s age or the natural chronological flow of Ezra 6 and 7 is mentioned. Anderson, out of a well-intentioned necessity to prove his interpretation of Daniel 9, simply ignored the biblical evidence, instead relying on unsubstantiated claims by another respected historian.

Unfortunately, historians and Bible scholars of the past two centuries have followed in Anderson’s footsteps. I encourage you to see for yourself. Take any popular book on the Second Temple era or the prophecy of Daniel 9, and you’ll find virtually no biblical chronological evidence for Ezra and Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era. What you will find instead are various forms of what I call the “Artaxerxes assumption.”

Lest you think I overstate my case, let’s look closer at this decree given by Artaxerxes to Nehemiah and see what the Bible’s own internal chronological evidence can tell us about it.

The Twentieth Year

First let’s look at the starting point of the decree given to Nehemiah. The chronology for this decree begins in the ninth month (Chisleu) of the twentieth year of Artaxerxes, when Nehemiah learned of the terrible conditions in Jerusalem. Hanani, one of Nehemiah’s brethren, brought news that the repatriated Jews in Jerusalem were being harassed by their enemies, due in part to the fact that the walls and gates of Jerusalem were broken down.

Nehemiah then petitions YHWH in a prayer reminiscent of Daniel’s wonderful pleadings for YHWH’s mercy found in Daniel 9:1–23. After Nehemiah’s prayer, in the first month (Nisan) in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes, Nehemiah makes his case to the king. (If you’re noticing a date discrepancy there, bear with me—we’re getting to it.) The king allows Nehemiah to leave his service as a cupbearer and gives a decree that Nehemiah may return to Jerusalem and repair its breaches. This repair of the walls of Jerusalem is what Anderson and many others after him have claimed to be the “commandment to restore and build” prophesied by Daniel.

The first obvious problem with this is the fact that Nehemiah learns of the news in the ninth month of twentieth year of Artaxerxes, but then approaches the king in the first month of the same year. Obviously, it makes no sense for Nehemiah to approach the king eight months before he even learned of the plight of his brethren in Jerusalem.

The words of Nehemiah the son of Hachaliah. And it came to pass in the month Chisleu, in the twentieth year, as I was in Shushan the palace . . . (Nehemiah 1:1)

And it came to pass in the month Nisan, in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes the king, that wine was before him: and I took up the wine, and gave it unto the king. Now I had not been beforetime sad in his presence. (Nehemiah 2:1)

Anderson tries to deal with this chronological difficulty by saying the reference in Nehemiah 1 refers to the ascension year of Artaxerxes, while Nehemiah 2 refers to his first year of sole rule. This may be one way to explain it, but my question is, why would the only prophecy in the Bible that requires a specific secular date for its starting point be based upon a secular date that cannot be determined with any degree of certainty? I mean, we are talking about the countdown to the Messiah, and the best the Bible can do is give us a decree with a confusing starting point?

Personally, I don’t believe the Bible shows us that YHWH works that way. To my way of looking at the congruency of the biblical record, the most important prophecy in the Bible—a prophecy specifically given as a chronological countdown—must have a clearly definable starting point commensurate with its importance.

So what does that mean? If none of the four options before us can be held with any certainty, what are we to conclude? Simply put, there must be another decree we are missing.

But before we look for such a decree, let’s first ensure we understand Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era, independent of Ezra. After all, we’ve already learned the peril of making assumptions! Does the Bible provide us any evidence as to the identity of Nehemiah’s mysterious Persian king Artaxerxes and thus the starting point of our countdown to the Messiah? Let’s look and see.

* * *

“The words of Nehemiah the son of Hachaliah. And it came to pass in the month Chisleu, in the twentieth year, as I was in Shushan the palace . . .”

Nehemiah 1:1

In 520 BC, nearly sixteen years after permission to build the temple had been given, the house of YHWH still lay in the initial stages of construction, with only some of the foundation stones to show for over a decade of effort. Seeing this neglect, YHWH stirred up the prophets Haggai and Zechariah to tell the people to return and build the temple. Four years later the temple in Jerusalem was completed, but very little progress had been made in building the walls of the ancient citadel. The remnant of people who dwelt there were still being harassed by their enemies.

Years later, back in Shushan, the winter palace of the Persian kings, our hero Nehemiah is the cupbearer to King “Artaxerxes.” Nehemiah hears of the plight of his brethren in Jerusalem and sets out to do something about it. After pouring his heart out to YHWH in prayer, Nehemiah petitions Artaxerxes to allow him to go up and repair the walls of Jerusalem. Artaxerxes grants his request, and we learn later that Nehemiah also becomes governor (Tirshatha) of Jerusalem for twelve years (Nehemiah 5:14).

As we saw in the previous chapter, many scholars today identify the Persian Artaxerxes in both the books of Ezra and Nehemiah as Artaxerxes Longimanus. But if you’ve taken a serious look at the information I’ve provided in the previous chapters on Ezra’s place in the Second Temple era, you have a better perspective on why I say such a conclusion is based upon virtually no biblical evidence. But what about the book of Nehemiah? Where does it stand in terms of the chronological evidence related to Ezra and Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era? I think the answer will surprise you.

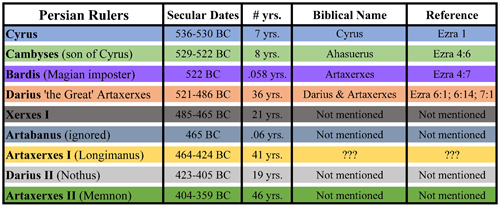

Governor of Jerusalem for Twelve Years

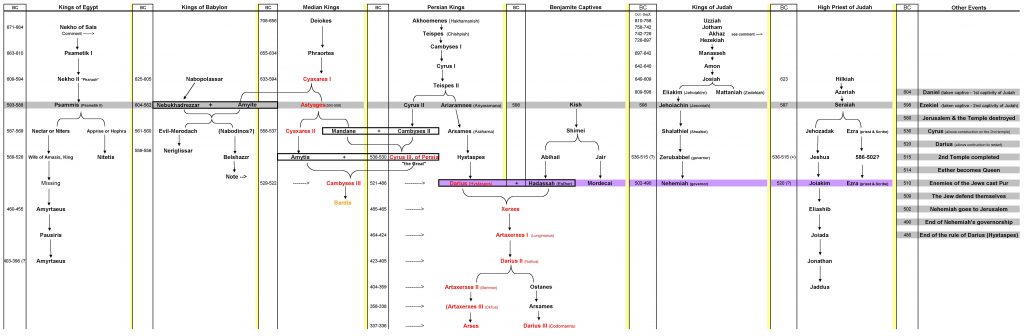

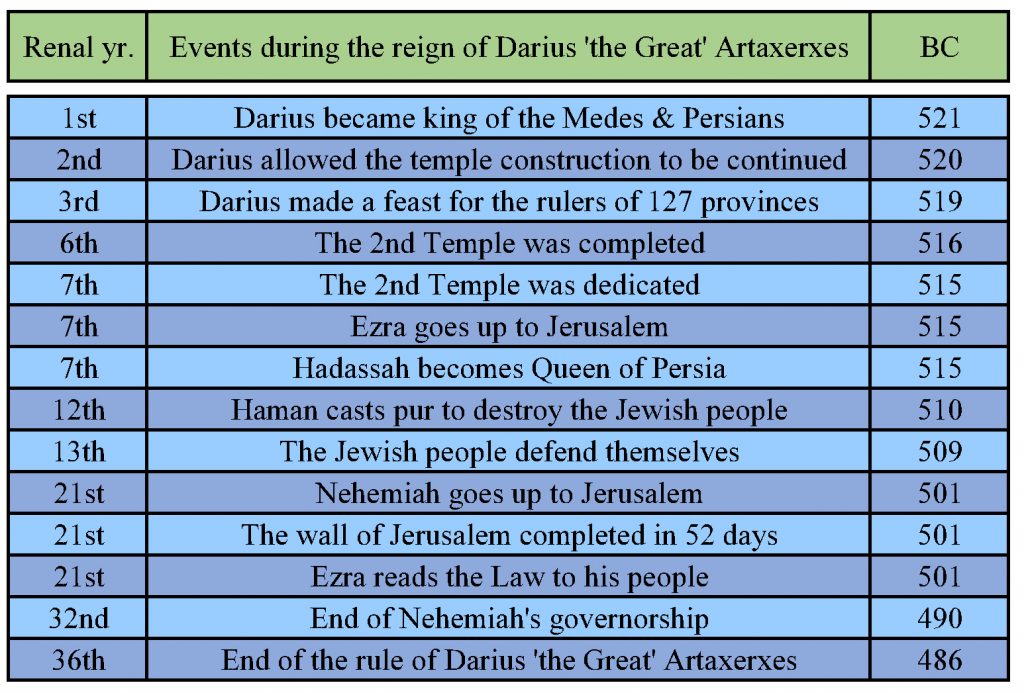

In Nehemiah 5:14, we read that Nehemiah was appointed governor from the twentieth to the thirty-second year of Artaxerxes. As we learned in chapter 5, this information is really helpful in our search for the Persian Artaxerxes of Nehemiah, because few Persian kings ruled for thirty-two years or longer. In fact, this chronological gem allows us to limit our search for Nehemiah’s Artaxerxes to just three Persian kings. Those kings are Darius ‘the Great’, Longimanus, and Memnon (see chart below).

Moreover from the time that I was appointed to be their governor in the land of Judah, from the twentieth year even unto the two and thirtieth year of Artaxerxes the king, that is, twelve years, I and my brethren have not eaten the bread of the governor. (Nehemiah 5:14)

So which of the above Persian kings could reasonably be seen as the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah? Again, most Bible scholars for centuries have placed these key stories in the reign of Longimanus, in 464–424 BC. But there are several additional pieces of evidence in the book of Nehemiah that build a totally different picture of Ezra and Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era than what is commonly supposed. Let’s take a look at this evidence.

So which of the above Persian kings could reasonably be seen as the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah? Again, most Bible scholars for centuries have placed these key stories in the reign of Longimanus, in 464–424 BC. But there are several additional pieces of evidence in the book of Nehemiah that build a totally different picture of Ezra and Nehemiah’s place in the Second Temple era than what is commonly supposed. Let’s take a look at this evidence.

Shushan, the Palace of the Kings of Persia

To set the stage in Nehemiah 1:1, we find Nehemiah in Shushan, the winter palace of Persia. For those familiar with the book of Esther, you know that Shushan was the palace of Esther’s King Ahasuerus. Keep this pertinent fact in mind, because it is very relevant to understanding the dynamics of why a Jewish man held the very important position of cupbearer to the king of Persia. In the next chapter, we will look at how an often overlooked piece of biblical evidence in the book of Nehemiah will alter our view of the Second Temple era and explain in part why the Jewish people had such a powerful presence in the affairs of Persia.

The Porter of the Gates

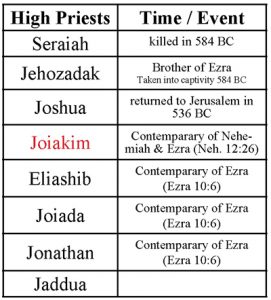

Our first substantial piece of chronological evidence related to Nehemiah comes from Nehemiah 12:25–26. This passage tells us that five porters of the gates of Jerusalem were contemporaries with Joiakim (the son of Joshua the high priest), Ezra, and Nehemiah.

Mattaniah, and Bakbukiah, Obadiah, Meshullam, Talmon, Akkub, were porters keeping the ward at the thresholds of the gates. These were in the days of Joiakim the son of Jeshua, the son of Jozadak, and in the days of Nehemiah the governor, and of Ezra the priest, the scribe. (Nehemiah 12:25–26)

Mattaniah, and Bakbukiah, Obadiah, Meshullam, Talmon, Akkub, were porters keeping the ward at the thresholds of the gates. These were in the days of Joiakim the son of Jeshua, the son of Jozadak, and in the days of Nehemiah the governor, and of Ezra the priest, the scribe. (Nehemiah 12:25–26)

This reference provides several helpful chronological synchronisms. First, it tells us plainly that Nehemiah and Ezra were contemporaries. The text goes even further by linking Ezra and Nehemiah with Joiakim the son of Joshua, the high priest, and five named porters. In 1 Chronicles 9:7 we find that two of these porters were among the repatriated Babylonian captives who returned to the land of Israel by the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC:

So all Israel were reckoned by genealogies; and, behold, they were written in the book of the kings of Israel and Judah, who were carried away to Babylon for their transgression. Now the first inhabitants that dwelt in their possessions in their cities were, the Israelites, the priests, Levites, and the Nethinims . . . And the porters were, Shallum, and Akkub, and Talmon, and Ahiman, and their brethren: Shallum was the chief. (1 Chronicles 9:1–2, 17)

And the rulers of the people dwelt at Jerusalem: the rest of the people also cast lots, to bring one of ten to dwell in Jerusalem the holy city, and nine parts to dwell in other cities . . . Now these are the chief of the province that dwelt in Jerusalem: . . . Moreover the porters, Akkub, Talmon, and their brethren that kept the gates, were an hundred seventy and two. (Nehemiah 11:1–3, 19)

Notice that in 1 Chronicles above, we are told that Shallum was the chief porter. In Ezra 10 we learn that Shallum the porter was one of the men of Jerusalem who had taken a non-Hebrew wife from among the inhabitants of the land. Shallum, along with the rest of the inhabitants of the land, agreed to put away their strange wives at the prompting of Ezra. According to the text, this all took place in the seventh and eighth years of Artaxerxes.

And Ezra the priest, with certain chief of the fathers, after the house of their fathers, and all of them by their names, were separated, and sat down in the first day of the tenth month to examine the matter. And they made an end with all the men that had taken strange wives by the first day of the first month. (Ezra 10:16–17)

What this means chronologically is that the same Shallum the chief porter, Akkub, and Talmon who came up to Jerusalem in 536 BC were still alive in the seventh year of a Persian Artaxerxes. Subsequently, Shallum is missing from the lists by the twentieth year of Artaxerxes. It is reasonable to assume that he had either died because of his obvious old age or was demoted because he had taken a wife of non-Hebrew origin. In any case, the above verses show that Shallum, Akkub, and Talmon most reasonably fit in the chronological context of the Second Temple as contemporaries of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes. By no reasonable biblical criteria could they have been alive by the seventh year of Artaxerxes Longimanus, or for that matter, nearly fourteen years later in the twenty-first year of Artaxerxes at the dedication of the wall.

Zerubbabel and Nehemiah, the Governors of Jerusalem

Next, let’s look at Nehemiah 12:47. This passage links the governorships of Zerubbabel and Nehemiah and the ministrations to the singers and porters.

And all Israel in the days of Zerubbabel, and in the days of Nehemiah, gave the portions of the singers and the porters, every day his portion: and they sanctified holy things unto the Levites; and the Levites sanctified them unto the children of Aaron. (Nehemiah 12:47)

Nehemiah 12 begins by listing the priests and Levites who came up out of captivity with Joshua and Zerubbabel in the first year of Cyrus. Then, in Nehemiah 12:27, it recounts the dedication of the finished wall of Jerusalem. Finally the chapter closes with the above verses, which clearly imply continuity in the temple service under the leadership of Zerubbabel and Nehemiah. This passage makes much more sense if we see Zerubbabel and Nehemiah as consecutive governors of Jerusalem from the days of Cyrus through to the days of Darius ‘the Great’, rather than inserting a gap of sixty-plus years between Zerubbabel and Nehemiah to account for the reign of Longimanus.

The First Sukkoth

Nehemiah 8 makes a fascinating statement regarding Israel’s observance of the biblical holy day of Sukkoth as it relates to the repatriated captives:

And all the congregation of them that were come again out of the captivity made booths, and sat under the booths: for since the days of Jeshua the son of Nun unto that day had not the children of Israel done so. And there was very great gladness. (Nehemiah 8:17)

Notice that it describes these people as “them that were come again [returned/shuwb] out of the captivity.” The most reasonable reading implies these people were the same generation as those who came up with Joshua and Zerubbabel in 536 BC. This places them as contemporaries of Darius ‘the Great’, also known as Artaxerxes. Indeed, this confirms the other chronological evidence we have found concerning Nehemiah and Ezra: namely, that they were first-generation contemporaries of those Jewish captives who returned to Jerusalem at the end of the 70 years of Babylonian captivity. Any other reading of the text strains the credibility of sound biblical interpretation.

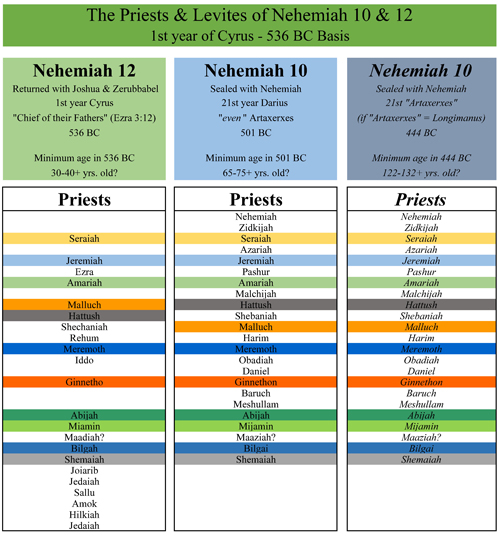

The Lists of Nehemiah 10 and 12

Our final piece of evidence—and the one that really ties up the chronology of Ezra and Nehemiah—is the lists of Nehemiah 10 and 12. Nehemiah 12 lists the priests and Levites, “chiefs of their fathers” (“ancient men” in Ezra 3:12), who came up out of the captivity with Joshua and Zerubbabel by the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC. In Nehemiah 10, at the dedication of the wall in Jerusalem in the twenty-first year of our mystery king Artaxerxes, we find many of these same priests and Levites alive and active. Take a look at a side-by-side comparison of Nehemiah 10 and 12 in the charts below. The names and their order are reproduced as given in the Scripture.

Which is the more reasonable explanation? These “chief men” were most reasonably sixty-five to seventy-five years old during the reign of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes or these men would have been at their youngest 122–132 years old during the reign of Artaxerxes Longimanus. Pretty compelling, isn’t it?

Which is the more reasonable explanation? These “chief men” were most reasonably sixty-five to seventy-five years old during the reign of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes or these men would have been at their youngest 122–132 years old during the reign of Artaxerxes Longimanus. Pretty compelling, isn’t it?

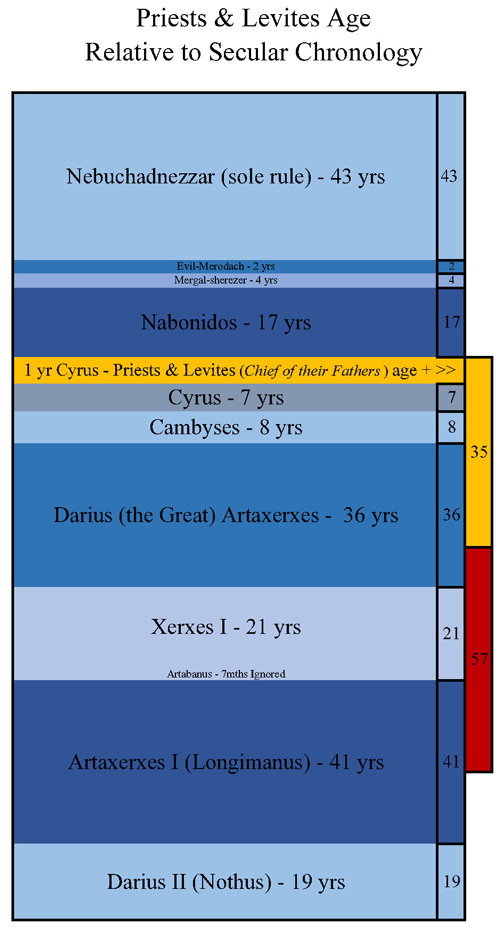

Please see the chart below for a relative perspective on the age of the priests and Levites in comparison to the secular chronology of Babylon and Persia. As you peruse the chart, keep Ezra 3:12 in mind. Some of these “chief men” were already “ancient” by the first year of Cyrus when the temple foundation was laid by Joshua and Zerubbabel.

But many of the priests and Levites and chief of the fathers, who were ancient men, that had seen the first house, when the foundation of this house was laid before their eyes, wept with a loud voice; and many shouted aloud for joy. (Ezra 3:12)

In summary, the most reasonable explanation of the evidence given in this chapter shows that Nehemiah and Ezra were contemporaries of Darius ‘the Great’, also known as Artaxerxes. Any other rendering of the chronology requires one to ignore the most reasonable and natural reading of the books of Nehemiah, Ezra, and Chronicles.

Testing the Fourth Decree

How does this commandment or decree given by Artaxerxes to Nehemiah stand in light of our four questions?

- Could this decree be considered a dabar or word to return and build Jerusalem?

- Did this decree cause the Jewish people to shuwb (return or turn back) and build Jerusalem?

- Was this building event of enough contextual relevance to constitute building Jerusalem?

- Can the date of this decree be firmly established in the Biblical and secular record?

Positives:

- In a general sense, rebuilding the walls of Jerusalem could be considered “building Jerusalem.”

- Nehemiah 2:18 does mention dabar in the context of Artaxerxes’s “words” to Nehemiah.

Negatives:

- Nehemiah, based upon the all available biblical evidence, was not a contemporary of Artaxerxes Longimanus. The Bible places him as a contemporary of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes. The date of this decree can be roughly placed in biblical chronology, but it leaves us short of Yeshua’s birth in a way we should consider troubling if this is indeed our starting point.

- Nehemiah was given permission to repair the walls and gates of Jerusalem, but Daniel 9:25 indicates that rebuilding the plaza and walls was to take place during the sixty-two weeks as part of the ongoing construction efforts, not as the initiating event.

- This decree by Artaxerxes in its most literal sense was not a word (dabar) for the Jewish people to return (shuwb) or turn back to the building efforts. This decree was given specifically to Nehemiah to build the walls of Jerusalem.

- There is some reasonable uncertainty about the exact date of this decree given by Artaxerxes.

In Closing

The Bible’s internal chronological evidence does not provide a reasonable basis upon which to claim Nehemiah was a contemporary of Artaxerxes Longimanus. Instead, it makes a compelling case that Nehemiah was in fact a contemporary of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes of Persia. Thus any interpretation of Daniel 9 which uses as its starting point a decree in the reign of the Longimanus can no longer claim its fulfillment in Yeshua. Further, because many today see Daniel 9 and the 70 weeks prophecy as part of a future eschatological framework, this erroneous Artaxerxes assumption has troubling implications for much of today’s popular eschatological thought.

By this time, our study may have radically challenged your understanding of this whole era. But what if I told you we were still missing a pivotal piece of evidence related to the Second Temple era and Nehemiah’s efforts to rebuild the walls of Jerusalem? Indeed, this is the case. For those willing to really dig into this subject the following is the history of a young Jewish maiden and how her courage changed the history of the Jewish people and influenced the very events we have been discussing in the past several blog posts.

* * *

“Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:) . . .”

Esther 1:1

To me one of the coolest statements in the book of Nehemiah is an often overlooked mention of the queen of Persia. It’s a statement that frankly seems out of place unless you understand the chronological context of the Persian era. In the past few chapters, we’ve learned that the Jewish people were shown amazing favor during the reign of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes. This king over 127 provinces went out of his way to financially support and encourage the construction of the temple of Jerusalem as well as the city itself. It turns out there is more to the story than most of us have realized, and the book of Nehemiah gives us a clue:

And it came to pass in the month Nisan, in the twentieth year of Artaxerxes the king, that wine was before him: and I took up the wine, and gave it unto the king . . . And the king said unto me, (the queen also sitting by him,) For how long shall thy journey be? and when wilt thou return? So it pleased the king to send me; and I set him a time. (Nehemiah 2:1–6, emphasis mine)

Kind of curious, isn’t it? Why do you think Nehemiah saw fit to include this seemingly irrelevant information about the queen of Persia? Why would his Jewish readers care about Artaxerxes’s Gentile queen? Well, this apparently trivial fact gives us a glimpse into the internal affairs of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes during the early years of his reign. The most likely reason the queen of Persia would be mentioned by Nehemiah is that his audience understood who he was referring to. As we will see, Nehemiah mentioned the queen of Persia because this was none other than the Jewish heroine Hadassah, or as she is commonly known, Esther. If you are skeptical, that’s understandable—many respected biblical scholars have claimed that Esther was the queen of the Persian king Xerxes I, Darius the Great’s successor. In the book of Esther itself he is merely called “Ahasuerus.” But what does the biblical record say?

As we learned in the past several chapters, the Bible provides reasonable if not conclusive evidence that Darius ‘the Great’ was also called Artaxerxes and that it was during his reign that the events of Ezra and Nehemiah took place. So here we find Nehemiah, cupbearer to Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes, asking the king for permission to return to Jerusalem and rebuild its walls. The text also informs us that the queen was present at this audience.

Artaxerxes = Ahasuerus?

Some might understandably challenge the notion that the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah is the same as the Ahasuerus of the book of Esther, but let’s withhold judgment until we’ve looked at all of the evidence.

First, it is important to once again note that “Ahasuerus” is a title given to Persian kings, much like the title “Artaxerxes.” As we saw in chapter 3, the Bible identifies Cyrus’s son Cambyses with the title of Ahasuerus, and Daniel 9 identifies a Darius “of the seed of the Medes” as the son of an Ahasuerus. Including the reference in Daniel 9, we have at least three Medes or Persians whom the Bible identifies with this title. The ISBE Bible Dictionary entry 297 explains:

297 Ahasuerus or Asseurus

<a-haz-u-e’-rus>, (Septuagint Grk: Assoueros, but in Tobit 14:15 Asueros; the Latin form of the Hebrew Heb: ‘achashwerosh, a name better known in its ordinary Greek form of Xerxes): It was the name of two, or perhaps of three kings mentioned in the canonical, or apocryphal, books of the Old Testament.

With this evidence in mind, neither Artaxerxes nor Ahasuerus should be understood as proper names, and as such they provide us little basis upon which to determine the identity of the Persian kings being mentioned in the biblical passages. As we have done with Ezra and Nehemiah, we will rely on the Bible’s internal chronological evidence as well as other circumstantial details to make our determinations.

Back to Shushan the Palace

In our efforts to determine the identity of the Persian Ahasuerus spoken of here in Nehemiah, let’s turn our attention to the location of these events. Nehemiah 1:1 and Esther 1:1–2 provide the details on Shushan, the palace of the Persian kings.

The words of Nehemiah the son of Hachaliah. And it came to pass in the month Chisleu, in the twentieth year, as I was in Shushan the palace . . . (Nehemiah 1:1, emphasis mine)

Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:) that in those days, when the king Ahasuerus sat on the throne of his kingdom, which was in Shushan the palace . . . (Esther 1:1–2, emphasis mine)

The above verses allow us to conclude that both events took place in the same location. But is the Artaxerxes of Nehemiah the same as the Ahasuerus of Esther? Take a look at the following biblical and secular sources and see what you think:

Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:) . . . (Esther 1:1 LXE, emphasis mine)

Now when Darius reigned, he made a great feast unto all his subjects, and unto all his household, and unto all the princes of Media and Persia, and to all the governors and captains and lieutenants that were under him, from India unto Ethiopia, of an hundred twenty and seven provinces. (1 Esdras 3:1 KJA, emphasis mine)

The great king Artexerxes unto the princes and governors of an hundred and seven and twenty provinces from India unto Ethiopia, and unto all our faithful subjects, greeting. (Ester 16:1 KJA (Greek), emphasis mine)

In the second year of the reign of Artaxerxes the great king, on the first day of Nisan, Mardochaeus the son of Jairus, the son of Semeias, the son of Chisaeus, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Jew dwelling in the city Susa, a grat [sic] man, serving in the king’s palace, saw a vision. Now he was of the captivity which Nabuchodonosor king of Babylon had carried captive from Jerusalem, with Jechonias the king of Judea. (Esther 1:1 LXE, emphasis mine)

In the fourth year of the reign of Ptolemeus and Cleopatra, Dositheus, who said he was a priest and Levite, and Ptolemeus his son, brought this epistle of Phurim, which they said was the same, and that Lysimachus the son of Ptolemeus, that was in Jerusalem, had interpreted it. In the second year of the reign of Artexerxes the great, in the first day of the month Nisan, Mardocheus the son of Jairus, the son of Semei, the son of Cisai, of the tribe of Benjamin, had a dream. (Ester 1:1–2 KJA (Greek), emphasis mine)

And the king levied a tax upon his kingdom both by land and sea. And as for his strength and valour, and the wealth and glory of his kingdom, behold they are written in the book of the Persians and Medes, for a memorial. And Mardochaeus was vicery to king Artaxerxes and was a great man in the kingdom, and honored by the Jews, and passed his life beloved of his nation. (Esther 10:1 LXE , emphasis mine)

Now, in the first year of the king’s reign, Darius feasted those who were about him, and those born in his house, with the rulers of the Medes, and princes of the Persians, and the toparches of India and Ethiopia, and the generals of the armies, of his hundred and twenty-seven provinces (Antiquities of the Jews 11:33, emphasis mine)

Mordecai, the Jew, in the Greek edition of Esther {Apc Est 11:1-12}, is said to have had a dream on the first day of the month of Nisan, in the second year of the reign of Artaxerxes the Great (or Ahasuerus or Darius, the son of Hystaspes), concerning a river signifying Esther and two dragons portending himself and Haman. 3484c AM, 4194 JP, 520 BC (Ussher, Annals of the World, p. 126 , section 1015, emphasis mine)

The first part of the celebration was given over to the hundred and twenty seven rulers of the hundred and twenty-seven provinces of his empire. (Louis Ginzberg, Legends of the Jews, XII “Esther—The Feast for the Grandees”)

And the elders of the Jews builded, and they prospered through the prophesying of Haggai the prophet and Zechariah the son of Iddo. And they builded, and finished it, according to the commandment of the God of Israel, and according to the commandment of Cyrus, and Darius, and [even] Artaxerxes king of Persia. (Ezra 6:14, emphasis and strikethrough mine)

Now after these things, in the reign of Artaxerxes king of Persia, Ezra the son of Seraiah . . . This Ezra went up from Babylon; and he was a ready scribe in the law of Moses, which YHWH God of Israel had given: and the king granted him all his request, according to the hand of YHWH his God upon him. (Ezra 7:1–6, emphasis mine)

The common thread of all the above references is that Darius ‘the Great’, also known as Artaxerxes or Ahasuerus, was the Persian king who ruled over 127 provinces from India to Ethiopia. This further strengthens the connection between the events at Shushan the palace as described in the book of Nehemiah and those described in the book of Esther.

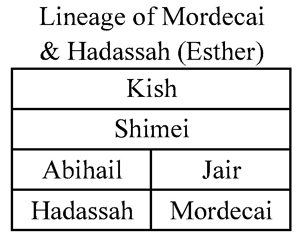

But as fascinating as the above circumstantial evidence might be, we still have not provided a solid chronological basis for it. For this evidence we turn to the lineage of Mordecai as found in Esther 2:5–6:

Now in Shushan the palace there was a certain Jew, whose name was Mordecai, the son of Jair, the son of Shimei, the son of Kish, a Benjamite; who had been carried away from Jerusalem with the captivity which had been carried away with Jeconiah king of Judah, whom Nebuchadnezzar the king of Babylon had carried away. (Esther 2:5–6)

Mordecai and Hadassah

Esther 2:5–6 gives the lineage of Mordecai through his great-great-grandfather Kish. The most reasonable reading of this passage shows that Kish, the great-great grandfather of Mordecai and Esther, was taken captive by Nebuchadnezzar at the same time as King Jeconiah of Judah in approximately the eighth or ninth year of Nebuchadnezzar (see 2 Kings 24:12–16, 2 Chronicles 36:10). Chronologically, this means there were eighty years between the start of Kish’s captivity (in the ninth year of Nebuchadnezzar) and the seventh year of Darius, 115 years between the ninth year of Nebuchadnezzar and the seventh year of Xerxes I, and 136 years to the seventh year of Artaxerxes I—Longimanus. Using the most reasonable metrics, we find that in order for Esther to be a young girl or damsel (na’arah, as she is called in the Hebrew text) in the seventh year of a Persian king, the most reasonable conclusion once again points us in the direction of Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes.

Some historians claim that it is Mordecai’s captivity, not Kish’s, that is in view in Esther 2:5–6, but this is not biblically plausible. As the chart above shows, Hadassah and Mordecai were of the same generation. Even if there was a great disparity in their ages, by no reasonable means could Hadassah have still been a na’arah by the reign of Darius ‘the Great’, and definitely not so by the eras of Xerxes I or Longimanus, if it was Mordecai’s captivity which was in view in the passage above. The chronology of the captivity leaves little doubt that Darius ‘the Great’ was Esther’s king.

Some historians claim that it is Mordecai’s captivity, not Kish’s, that is in view in Esther 2:5–6, but this is not biblically plausible. As the chart above shows, Hadassah and Mordecai were of the same generation. Even if there was a great disparity in their ages, by no reasonable means could Hadassah have still been a na’arah by the reign of Darius ‘the Great’, and definitely not so by the eras of Xerxes I or Longimanus, if it was Mordecai’s captivity which was in view in the passage above. The chronology of the captivity leaves little doubt that Darius ‘the Great’ was Esther’s king.

A Generational Comparative

For visual people like myself, the following chart may help you wrap your mind around the contemporaneous relationships of Esther, Nehemiah, and Ezra and the kings of Persia, Media, Babylon, and Judah. This chart is based upon the work of Richard Edmund Tyrwhitt in his 1868 book Esther and Ahasuerus. I have modified it to include Ezra and Nehemiah as well as the high priests of Judah. For those interested in the subject of Esther and her king, I heartily recommend Tyrwhitt’s two-volume work on the subject.

Darius the Huckster

A final piece of evidence regarding Darius’s place in the Second Temple era comes from the historian Herodotus, who records that Darius established a revolutionary form of tribute that allowed his subjects to provide goods or commodities in lieu of gold and silver (Herodotus iii:89). This earned Darius the somewhat ignoble title of “Huckster” from Herodotus. It is fascinating to see this confirmed in the books of Esther, Ezra, and Nehemiah. The Darius of Ezra 6 and the Darius “even” Artaxerxes of Ezra 7 did indeed provide material support to the Jewish people from the king’s treasure house in the form of commodities, not just money:

And the king Ahasuerus laid a tribute upon the land, and upon the isles of the sea. (Esther 10:1)

Then Darius the king made a decree . . . Moreover I make a decree what ye shall do to the elders of these Jews for the building of this house of God: that of the king’s goods, even of the tribute beyond the river, forthwith expenses be given unto these men . . . And that which they have need of, both young bullocks, and rams, and lambs, for the burnt offerings of the God of heaven, wheat, salt, wine, and oil, according to the appointment of the priests which are at Jerusalem, let it be given them day by day without fail. (Ezra 6:1–9, emphasis mine)

Now after these things, in the reign of Artaxerxes king of Persia, Ezra the son of Seraiah . . . This Ezra went up from Babylon . . . And whatsoever more shall be needful for the house of thy God, which thou shalt have occasion to bestow, bestow it out of the king’s treasure house. And I, even I Artaxerxes the king, do make a decree to all the treasurers which are beyond the river, that whatsoever Ezra the priest, the scribe of the law of the God of heaven, shall require of you, it be done speedily, unto an hundred talents of silver, and to an hundred measures of wheat, and to an hundred baths of wine, and to an hundred baths of oil, and salt without prescribing how much. (Ezra 7:1–6, 7:20–22, emphasis mine)

The Power of Persia

At the height of Persian power and influence, Darius ‘the Great’ Artaxerxes ruled over 127 provinces, and Hadassah (Esther) became his queen. Think about the implications of this information! During the reign of Darius ‘the Great’, a young Jewish woman was queen. Mordecai, Hadassah’s cousin, was the second most powerful man in Persia. Nehemiah was cupbearer. Josephus even notes that Zerubbabel, who preceded Nehemiah as governor of Jerusalem, was a bodyguard to the king. This whole picture explains in part the magnanimity of Darius toward the Judean captives’ efforts in rebuilding their temple and city. These very same people were some of his most trusted and loyal subjects.

As a side note, Haman’s Agagite lineage—a people group with a history of bad blood with the Jews—is often pointed to when explaining his seemingly unjustified hatred of the Jewish people. Now you know the rest of the story. Haman was a power-hungry man, and the Jewish people were clearly a threat to his plans during the rise of Darius ‘the Great’ to the pinnacle of Persian power and influence.

The following chart provides a chronological timeline of the events found in the books of Ezra, Nehemiah, and Esther as we’ve explored in the past few chapters. As you look at the timeline, consider the impact Hadassah’s efforts had in protecting her brethren throughout the Persian empire. Had she not acted as she did, Ezra, the Judean repatriates, and the very Second Temple itself might have become victims of Haman’s evil machinations.

Persia and the Coming Messiah

It’s fascinating to me to see how YHWH used a secular nation like Persia to play such an important role in the history of the Jewish people. Persia at the height of its power was used by YHWH to restore His people to the land of Israel and rebuild His desolate sanctuary. It is intriguing to note that Britain was the world power of our generation which brought about the return of the Jewish people to the land of Israel after nearly two thousand years of desolations. Even more fascinating, it is the US (once a subject of British rule) that has now taken the mantle of leadership on the world stage, and indeed, our very own government has inserted itself into the current affairs concerning the Jewish people and Jerusalem. Watch in coming years for the world powers involving themselves in the affairs of the Jewish people, Jerusalem, and the Third Temple. As Mark Twain is quoted as saying, “History doesn’t repeat itself, but it does rhyme.”

Though the events described in the past few blog posts were incredibly important to understanding the four Persian commandments to restore and build Jerusalem, our quest to find the starting point to the countdown to the Messiah is not finished. None of those four Persian decrees totally satisfied the contextual criteria of the “word to return and build Jerusalem” of Daniel 9:25. As I have said, there must be a decree we are overlooking—and indeed, there is. The final decree or commandment we will look at is in fact the focal point of all these events, and yet it has been all but ignored by biblical scholars. What I’m talking about is the little known fifth decree to return and restore.

I hope you continue the adventure with me next time as we look at this most important Fifth Decree.

* * *