Does the Bible really give an accurate description of Darius I ‘The Great’ of Persia?

Does the Bible really give an accurate description of Darius I ‘The Great’ of Persia?

In this week’s article I’ll be comparing what the Bible says about Darius with what Darius says about himself from his own royal inscriptions. My purpose of this week’s article is twofold. First, I hope to further impress upon you the credibility of the Bible and the accuracy with which it describes history. Second, I want to finish providing you with a complete picture of how the book of Ezra and Nehemiah describe this great Persian king.

As you will see, this information will provide us with some of the final pieces of background context which will help us in our next article to determine the historical relationship between Darius I and the Biblical Esther. Was Darius I Esther’s father in law or her husband? Has traditional Biblical scholarship once again depended too much on what secular historians have written and too little on the Bible’s own historical and chronological details? I believe so and I hope in the next several articles to show you why this is the case.

In the article of this series to date I’ve argued that the book of Ezra can be depended upon to provide the reader with straight forward and chronological details about Biblical history. If this is in fact an accurate statement, doesn’t it lend confidence to the reader that the book of Esther might also provide dependable chronological and historical details as well? I believe so, and I think you’ll find that evidence compelling.

But before we explore the question of Esther and her king, let’s first finish developing a complete picture of what the Bible says about Darius I – the great Persian king who the it also describes as an Artaxerxes. (For more context on the Persian word Artaxerxes please see last week’s article Darius and the Kingdom of Arta).

From Cyrus to Darius

For those just joining this exploration of Biblical history, this is part V in a series in which I am attempting to answer the challenges and criticisms raised by Rich Lanser of the respected organization Associates for Biblical Research in his article The Seraiah Assumption. In his article, Mr. Lanser vigorously disputes my view of 2nd temple history as it relates to Darius ‘The Great’ as described in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah. In the links below I’d encourage you to read Mr. Lanser’s article The Seraiah Assumption as well as my responses to specific points of criticism that Mr. Lanser has raised in his article. I’d also encourage you to read Mr. Lanser’s updated thoughts in an addendum to that article that he recently published in response to and email exchange we’ve had as well as his responses to some of the points I’ve made in these articles.

Articles related to this series:

The Seraiah Assumption by Rick Lanser of Associates for Biblical Research

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping up Loose Ends by Rick Lanser

My response to Rick Lanser’s – The Seraiah Assumption:

Introduction – The Associates for Biblical Research Responds to the Artaxerxes Assumption

Part I – Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4

Part II – Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem

Part III – Darius the great Persian Artaxerxes: A Contextual Look at the Book of Ezra in the Light of Persian History

Part IV – Darius and the Kingdom of Arta

Part V – Darius, Artaxerxes, & the Bible: Confirming Royal Persian Titulature

Part VI – Mordecai & the Chronological Context of Esther

Part VII – Esther, Ahasuerus, & Artaxerxes: Who was the Persian King of 127 Provinces?

Part VIII – Darius I: A Gentile King at the Crux of Jewish Messianic History

Part IX – The Priests & Levites of Nehemiah 10 & 12: Exploring the Papponymy Assumption

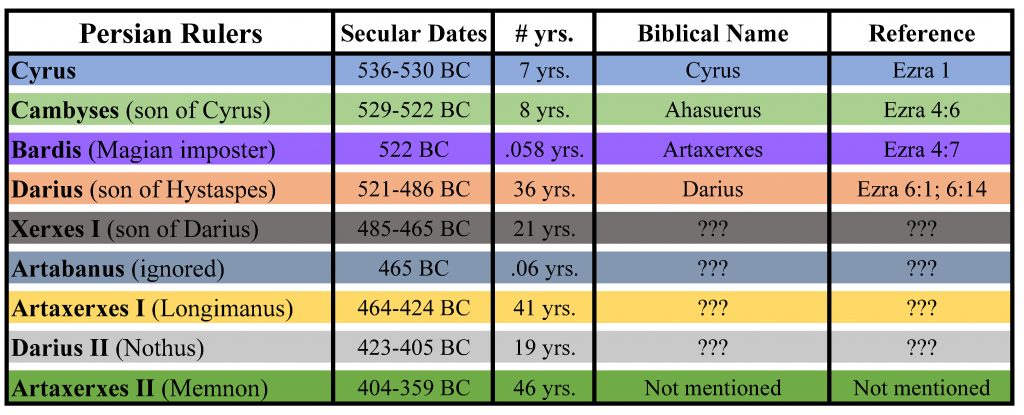

To briefly recap what we’ve explored chronologically so far, to date we’ve followed the Biblical history of the Jewish people, their captivity in Babylon for 70 years, and the decree of Cyrus which allowed them to return to Jerusalem and build the city and Yahweh’s desolate sanctuary.

The book of Ezra opened with Cyrus’ decree and Jewish people’s return to Jerusalem under the leadership of Joshua and Zerubbabel. We learned that the Jewish people only got as far as laying some of the foundation stones for the temple before their own lack of zeal and the harassment of their enemies stop their construction efforts.

As the book of Ezra describes it, the enemies of the Jewish people, between the reign of Cyrus and Darius I, hired counselors (think lobbyists) to harass them at every opportunity. After Cyrus died and a new Persian king (whom the Bible describes by the title or name Ahasuerus – Ezra 4:6) came to power these counselors approached this Persian king in an effort to stop construction. When this effort did not produce results they bided their time until years later when a new Persian king whom the Bible describes by the title Artaxerxes came to power. This Persian king did in fact listen to Jewish people’s enemies and he ordered the construction of Jerusalem stopped. As Ezra 4 describes it:

Now when the copy of king Artaxerxes’ letter was read before Rehum, and Shimshai the scribe, and their companions, they went up in haste to Jerusalem unto the Jews, and made them to cease by force and power. Then ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia. (Ezra 4:23-24)

It’s worth noting here once again that in Ezra 4 the enemies of the Jewish people, in their petition to Artaxerxes, describe the construction efforts as building Jerusalem but when they receive their cease and desist from Artaxerxes it was the temple construction which stopped. In other words, the account of Ezra 4 shows that the temple construction was in fact building Jerusalem.

Also note, as explained in Part III of this series Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4, that the use of the Aramaic word ‘edayin’ (now/then) as a chronological synchronism in Ezra 4:23 & 24 provide strong evidence that the history of Ezra 4 is straight forward historical – chronological account of Persian history from Cyrus to Darius.

Now [after these things] the copy of king Artaxerxes’ letter was read before Rehum, and Shimshai the scribe, and their companions, they went up in haste to Jerusalem unto the Jews, and made them to cease by force and power.

Then [after these things] ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia. (Ezra 4:23-24)

Authors Note: Please note that Mr. Lanser in his Addendum to his original article The Seraiah Assumption has provided additional information about his understanding of the word ‘edayin’ and its use here in Ezra 4 among other subjects. I’d encourage you to read that information. At the end of this article I will be explaining why I believe his explanation falls short and I’ll further be explaining how his errors regarding this subject are once again rooted in part in his misunderstanding of my position on the subject. Please see Mr. Lanser’s article here: The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping Up Some Loose Ends

What the context of Ezra 4 tells us is that there are two additional Persian kings between Cyrus and Darius. Because the Aramaic word ‘edayin’ consistently describes successive chronological information in the Bible we must see the Ahasuerus and Artaxerxes of Ezra 4:6 & Ezra 4:7-23 as Persian kings who ruled between the reigns of Cyrus and Darius. This in fact agrees with Persian history. Further the history in Ezra 4 provides some neat historical details that show the author of Ezra had an intimate understanding of Persian history from that era.

There are a couple places where this is confirmed. Our first example comes from Cambyses (likely Ahasuerus of Ezra 4:6) who did not stop construction of the temple when petitioned by the enemies of the Jewish people. Historically we know that Cambyses for the most part kept with his father’s tradition of restoring religious monuments of the peoples he ruled.

On the other hand, we know that the Persian king who followed Cambyses, Bardia (a.k.a Gaumâta/Smerdis) the Magian userper, who according to Darius’ own Behistun inscription, was responsible for the destruction of “the Temples” the previous kings had allowed. So when Ezra 4:7-24 describes an “Artaxerxes” who stopped construction on the temple of Jerusalem after the reign of Cyrus but before the reign of Darius, it confirms Darius I own account of this Magian usurper who he deposed. A king who, unlike Darius, had no reverence for the religious monuments of the people who he ruled. I quote from Darius’ cuneiform inscription on the cliffs of Behistun:

Murder of Smerdis and Coup of Gaumâta the Magian

[i.10] King Darius says: The following is what was done by me after I became king. A son of Cyrus, named Cambyses, one of our dynasty, was king here before me. That Cambyses had a brother, Smerdis by name, of the same mother and the same father as Cambyses. Afterwards, Cambyses slew this Smerdis. When Cambyses slew Smerdis, it was not known unto the people that Smerdis was slain. Thereupon Cambyses went to Egypt. When Cambyses had departed into Egypt, the people became hostile, and the lie multiplied in the land, even in Persia and Media, and in the other provinces.

[i.11] King Darius says: Afterwards, there was a certain man, a Magian, Gaumâta by name, who raised a rebellion in Paišiyâuvâdâ, in a mountain called Arakadriš. On the fourteenth day of the month Viyaxananote did he rebel. He lied to the people, saying: “I am Smerdis, the son of Cyrus, the brother of Cambyses.” Then were all the people in revolt, and from Cambyses they went over unto him, both Persia and Media, and the other provinces. He seized the kingdom; on the ninth day of the month Garmapadanote he seized the kingdom. Afterwards, Cambyses died of natural causes.

[i.12] King Darius says: The kingdom of which Gaumâta, the Magian, dispossessed Cambyses, had always belonged to our dynasty. After that Gaumâta, the Magian, had dispossessed Cambyses of Persia and Media, and of the other provinces, he did according to his will. He became king.

Darius kills Gaumâta and Restores the Kingdom

[i.13] King Darius says: There was no man, either Persian or Mede or of our own dynasty, who took the kingdom from Gaumâta, the Magian. The people feared him exceedingly, for he slew many who had known the real Smerdis. For this reason did he slay them, “that they may not know that I am not Smerdis, the son of Cyrus.” There was none who dared to act against Gaumâta, the Magian, until I came. Then I prayed to Ahuramazda; Ahuramazda brought me help. On the tenth day of the month Bâgayâdišnote I, with a few men, slew that Gaumâta, the Magian, and the chief men who were his followers. At the stronghold called Sikayauvatiš, in the district called Nisaia in Media, I slew him; I dispossessed him of the kingdom. By the grace of Ahuramazda I became king; Ahuramazda granted me the kingdom.

[i.14] King Darius says: The kingdom that had been wrested from our line I brought back and I reestablished it on its foundation. The temples which Gaumâta, the Magian, had destroyed, I restored to the people, and the pasture lands, and the herds and the dwelling places, and the houses which Gaumâta, the Magian, had taken away. I settled the people in their place, the people of Persia, and Media, and the other provinces. I restored that which had been taken away, as is was in the days of old. This did I by the grace of Ahuramazda, I labored until I had established our dynasty in its place, as in the days of old; I labored, by the grace of Ahuramazda, so that Gaumâta, the Magian, did not dispossess our house.

[i.15] King Darius says: This was what I did after I became king.

As you can see this inscription by Darius provides really neat confirmation of the Biblical account. The following chart provides an overview of the succession from Cyrus to Darius:

In Part III of this series, Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem as described in Ezra 5 we learned that the Jewish people in obedience to the divine command of Yahweh through the prophets Haggai and Zechariah, in the 2nd year of Darius, defied the previous decree of Artaxerxes (Bardis/Gaumâta?) the Magian usurper (who stopped construction of the temple) and they restarted their building efforts. With Darius’ blessing, four years later in Darius’ 6th year their efforts to rebuild the temple were successful.

In Ezra 6 by following the same straight forward interpretive principles that we applied to Ezra 4 & 5, we learned that the Bible in Ezra 6:14 informed us that Darius was also known by the Persian title “Artaxerxes”. This fascinating historical detail, overlooked by so many Biblical scholars, fundamentally changes how we see the history described in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah.

Instead of a nearly 60 year gap between Ezra 6 & 7 we find chronological continuity. For we see that Ezra 6 ends with the completion of the temple in the 6th year of Darius “even” Artaxerxes and then Ezra 7 opens in the 7th year of this same Artaxerxes, with Ezra, now that the temple was completed and dedicated, heading to Jerusalem to teach his people the Torah.

Shimshai the Scribe

Let me give you a fascinating historical example which confirms Ezra 6 & 7 and the Biblical identity of Darius even Artaxerxes. In Ezra 4:6-8, 23 the Bible describes a character who was part of the efforts to harass the Jewish people during the reign of “Artaxerxes” (Bardis/Gaumata). This individual’s name was Shimshai the scribe. Did you know that we have a cuneiform tablet that names a Shimshai? The only problem is the tablet in which he is named is dated to the reign of Cambyses not the reign Artaxerxes I (Longimanus). And since Biblical scholars have dated the Artaxerxes of Ezra 4:6-8, 23 to reign of Artaxerxes I (Longimanus) there is a 60 years gap between when the tablets say this man lived and when Biblical scholars believe he lived. Here read for yourself.

The following quote comes from Xerxes and Babylonia: The Cuneiform Evidence as published in the Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta edited by Caroline Waerzeggers and Maarja Seire page 45-47. I quote:

The formulary of Text 2 is characteristic of a transcript of a trial: a formal address by a plaintiff is followed by the questioning of the defendant by the judge and the defendant’s confession. The broken lines that follow expectedly contained the sentence. The trial was held in the presence of four men, including one judge. The name of the first man — hence the most important one — is partly damaged, just like his function, provided it was given at all. His filiation seems to have been skipped, which could indicate that he was a man of high standing, whose identity was obvious. The second person in the list, the judge Mušēzib-Bēl of the Aḫu-bāni family is, to my knowledge, unattested elsewhere in the published contemporary court documents. Judges Rēmūt-bēl-ilāni (active under Neriglissar in Babylon), and Nabû-rā’im-šarri (attested in Nabonidus’ second year in Tapsuḫu) were members of the same clan and since judicial functions were often passed in families, Mušēzib-Bēl’s link to one of them appears plausible.25 The fourth man present at the trial was Aštakka’, whose name is non-Babylonian. It is, however, the third person in the list, Šamšāya, who is the most intriguing member of the panel.

Šamšāya’s function bēlṭēmi(‘bearer of the report, chancellor’) is extremely rare in Neo- and Late Babylonian material. Holders of this title are found in only three cuneiform texts from the Persian period; two of them were drafted in circles close to Persian governors. The earliest known bēlṭēmi appears on a list of silver allotments issued to over eighty men engaged in the preparation of a visit of Cambyses in southern Babylonia in the second year of his reign (Moore 1939 no. 89).26 The official’s name is damaged, but he is described as “a Median, bēlṭēmi, who discussed the issue of sheep with Gūbaru.”27 He received a large sum of silver (0.5 mina), exceeding by far the allotments of other men. The second attestation of this title comes from Stolper 1989 no. 1 (BM 74554), a receipt for barley issued at the order of the governor of Babylon and Across-the-River, and Libluṭ and Gadalâma, two men described as sepīru bēlṭēmi (‘Aramaic scribe [and] chancellor’). The third attestation comes from a fragmentary tablet BM 67669 drafted during the reign of Darius I, where bēl ṭēmi appears next to members of the board of the Ebabbar temple of Sippar.

Bēlṭēmi is possibly a Neo-Assyrian term that entered Aramaic and consequently Persian chancellery parlance.28 It is found in the Arsames correspondence from Egypt, where similarly to Stolper 1989 no. 1 (BM 74554), concurrent use of the titles bēlṭēmi and sepīru (b῾lṭ῾m spr᾿ ‘chancellor [and] scribe’) is attested.29 In Egyptian and Bactrian Aramaic letter subscripts, b῾lṭ῾m is paralleled by a title yd῾ṭ῾m᾿znh ‘(PN) knows this order’, which in Bactrian letters is, again, borne by scribes (spr᾿).30 Similar correspondence may also be traced in Persepolis tablets.31 In Egypt, b῾lṭ῾m was a member of the satrap’s entourage, in charge of official correspondence.32 A notable attestation of bēlṭēmi comes from Ezra 4: 8–9, 23, which quotes a letter sent to king Artaxerxes by Rehum b῾lṭ῾m and Shimshai spr᾿ together with “their colleagues the judges[knwthwndyny᾿], legates[᾿prstky᾿], officials [ṭrply᾿],33Persians, men of Erech, Babylonians, men of Susa, that is Elamites.”34 The Septuagint’s rendering of the names of the two first officials as Raoumos and Samsaios suggests the original reading of the second one as Shamshai (rather than Shimshai).

The patronymic of Šamšāya, son of Bēl-iqīša, is Babylonian, but his own name is less straightforward. It is uncommon in Babylonian sources. It may be interpreted as a Kosename‘My sun’35 or a hypocorism of a longer name comprising the theophoric element Šamaš. Alternatively, it may be a West Semitic appellative of a similar meaning. The only eminent bearers of this name were the royal resident of the Ebabbar temple at Sippar, attested in the twenty-sixth year of Darius I,36 and the son of Tattenai, the governor of Accross-the-River in the latter part of Darius I’s rule.37 No connection between these namesakes and the bēlṭēmi of Text 2 can be established.

It is much more inviting to identify Šamšāya with Shimshai the spr᾿, the colleague of Rehum b῾lṭ῾m of Ezra 4. Their names bear striking resemblance. Their titles admittedly vary (Šamšāya is called bēlṭēmi, while Shimshai a spr᾿), but both Stolper 1989 no. 1 (BM 74554) and the Aramaic material show that the two titles were occasionally combined. Also, a shift of titles between two protagonists of Ezra 4: 8–9, 23 in the course of the editorial process could be assumed. Both Šamšāya and Shimshai belonged to the elite of local Persian administration: Šamšāya stood close to the governor of Babylon and Acrossthe-River, while Shimshai, along with his colleague Rehum, addressed the king directly and implemented his orders. Both of them are listed next to judges. Furthermore, Ezra 4 contains many elements that reveal its editor’s acquaintance with the Persian-Babylonian administration and legal parlance.38 An obvious difficulty that this identification involves is a gap of over sixty years between Text 2 and the events set by Ezra-Nehemiah in the times of Artaxerxes (I). The authenticity of this so-called Artaxerxes correspondence in Ezra is a matter of dispute. According to extreme opinions, it was either a product of a Hellenistic author,39 or a compilation put together by an editor who had original sources from the Persian period at his disposal.40 If we accept the latter possibility, we may also allow that the editor of Ezra-Nehemiah has placed Rehum and Shimshai in the times of Artaxerxes I for reasons of narrative or ideological consistency, or simply by mistake. A possibility may thus be considered that Šamšāya bēlṭēmi,a high official in the satrapy of Across-the-River under Cambyses, served as a model for Shimshai/Shamshai of Ezra-Nehemiah.

22 CAD B, 261–263.

23 For Aramaic, see Lemaire and Lozahmeur 1987, for Neo-Babylonian, see Zadok 1985, 76–77.

24 Cf. Musil 1927, 313.

25 For Rēmūt-bēl-ilāni, see Wunsch 2000, 586, for Nabû-rā’im-šarri, see TBER no. 58 and its duplicate 59: 27.

26 For the context of the text, see Tolini 2009.

27 I˹x˺[x x]˹x˺ lúma-da-a-aen ṭè-e-mušáa-namuḫ-ḫiudu.níta a-naIgu-ba-ruiq-bu-ú (lines 41–42).

28 Stolper 1989, 301, Schwiderski 2000, 191.

29 Porten 1968, 56, Porten et al. 1996, 121 n. 74. Schwiderski’s proposition (2000, 190–193 and 358–359) to distinguish between a title(spr᾿) and an ad hoc function (b῾lṭ῾m) is problematic in view of the occurence of bēlṭēmi as name apposition, parallel to the title ‘judge’, in BM 47479. Also his argument that bēlṭēmi is never preceded by the determinative lú (2000, 192–193) is no longer standing: such writing (lúen ṭè-mu) is found in BM 67669.

30 Tuplin 2013, 128–130.

31 Tavernier 2008, 73.

32 Porten 1968, 55. For a possible correspondence between the b῾lṭ῾m and the Demotic senti, see Vittmann 2009, 102.

33 Or: ‘men from (Syrian) Tripoli’ (Koehler, Baumgartner and Stamm 2000, 1886b).

34 The translation follows Blenkinsopp 1988, 109.

35 Stamm 1939, 242.

36 Bongenaar 1997, 50.

37 Jursa and Stolper 2007, 249.

38 Especially line 9 is strongly influenced by Persian-Babylonian legal phraseology. The word knt ‘colleague, companion’ is commonly regarded as a borrowing from Akkadian (Porten et al. 1996, 159 n. 15, Koehler, Baumgartner and Stamm 2000, 1900a). Its only biblical occurrences are found in Ezra 4, 5 and 6; all of them refer to the companions of the opponents of the Jewish returnees (Rehum and Shimshai, Tattenai and Shethar-bozenai). Not only the word, but also the practice of combining it with professional titles might be traced to Akkadian (for references, see CAD K, 382). See especially the constructions parallel to knwthwndyny’‘(Shimshai and Rehum and) their colleagues the judges’: PN ukinattēšudayyānē(šašarri)‘PN and his colleagues the (royal) judges’ (BM 30957: 8–9, BM 62918: 2, Dar. 410: 5, MacGinnis 2008, 88–89: 1–2, Zadok 2002 no. D.4: 31, cf. Jursa, Paszkowiak and Waerzeggers 2003/2004 no. 1: 14). Similar practice of combining the Aramaic equivalent of the word kinattu with professional titles is found in Elephantine papyri (Porten et al. 1996, 159).

39 E.g. Schwiderski 2000, 381–382, Wright 2005, 39–43. 40 E.g. Grabbe 2006, 562–563, Williamson 2008, 52.

May I be so bold as to suggest another solution to the problem as presented by the authors above? Instead of the author of Ezra being mistaken or a later editor adding to the work and inserting this information 60 years after it happened, how about we just take the Bible’s chronology at face value, assuming the author of Ezra knew what he was talking about and admitting we just don’t understand all the pertinent details of Persian history as well as we supposed. Ezra 6 describes Darius I ‘The Great’ as an “Artaxerxes”, because this name was used as a throne name by Darius’ grandson Longimanus we assume this must be the only way this word was used in Persian history. The Bible tells us differently, and if we listen we find it places real historical people by the same name as described in the Bible in the very same time frame.

The more I study the chronology of the Bible, the more I am struck by how accurately it describes history. I’ve learned over the years when something doesn’t seem to make sense, it is better to assume that I just don’t have all the information I need, rather than assume the Bible got it wrong. The history described in the books of Ezra and Nehemiah proves this is a compelling way. Let me give you several more examples.

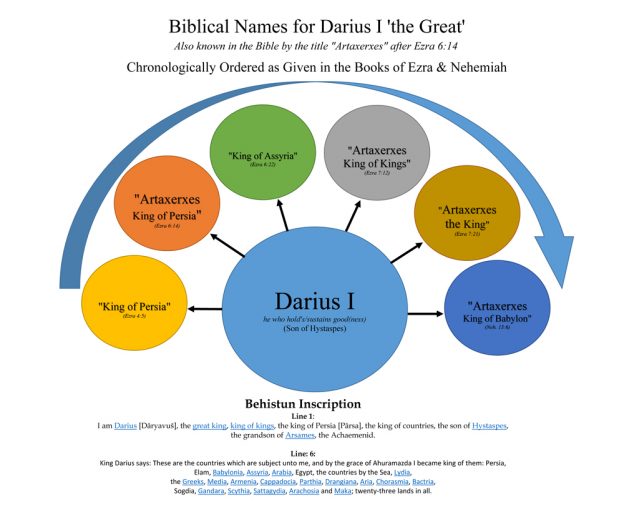

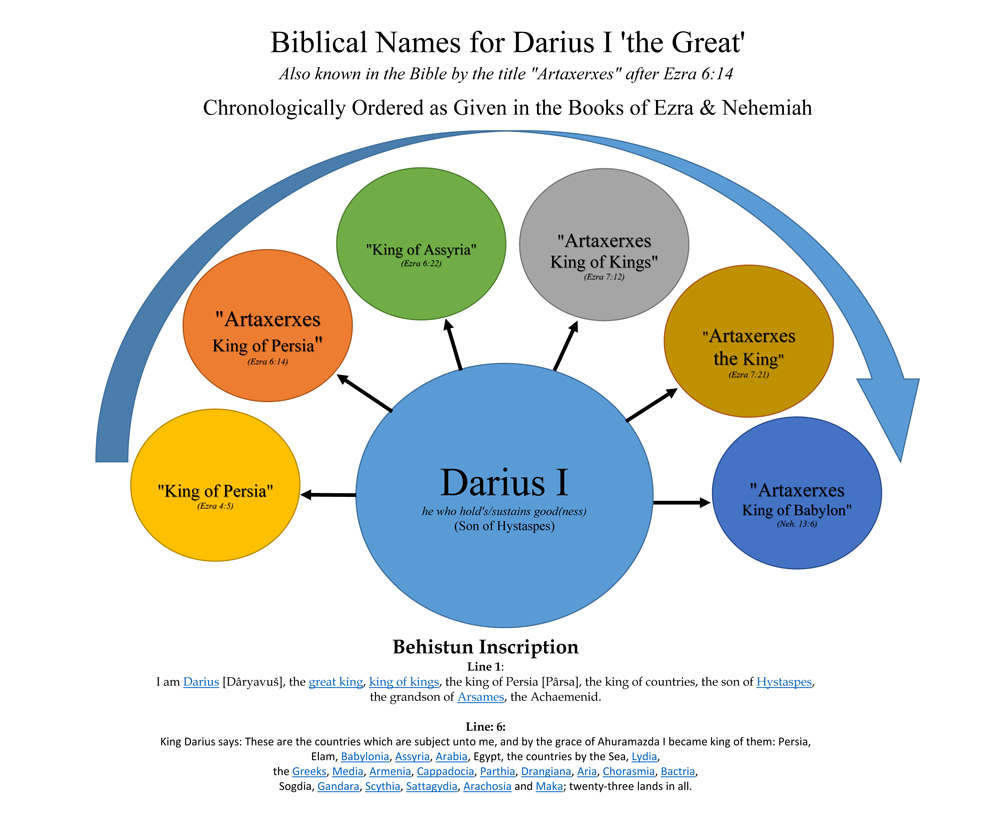

The Titles of Darius

Let’s do an experiment. For the sake of this exercise let’s assume the Bible’s chronology as described in the book of Ezra is a straight forward and chronologically congruent rendering of Persian history. In other words, it chronologically describes real Persian history between the reigns of Cyrus and Darius. This, what I have shown in these articles to be a reasonable working assumption, informs us that the “Artaxerxes” of Ezra 6:14 onwards and the “Artaxerxes” of Nehemiah are in fact a reference to Darius I ‘The Great’. Using this as our premise let me show just how accurately the Bible describes the titles by which Darius is known from his own royal inscriptions.

- King of Persia

- 24 Then ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia. (Ezra 4:24)

- 14 And the elders of the Jews builded, and they prospered through the prophesying of Haggai the prophet and Zechariah the son of Iddo. And they builded, and finished it, according to the commandment of the God of Israel, and according to the commandment of Cyrus, and Darius, and [even] Artaxerxes king of Persia. (Ezra 6:14)

- Now after these things, in the reign of Artaxerxes king of Persia, Ezra the son of Seraiah, the son of Azariah, the son of Hilkiah, (Ezra 7:1)

- Line 1 of Darius’ Behistun Inscription

I am Darius [Dâryavuš], the great king, king of kings, the king of Persia [Pârsa], the king of countries, the son of Hystaspes, the grandson of Arsames, the Achaemenid.

- King of Babylon

The use of the title “king of Babylon” in the book of Ezra and Nehemiah is a fascinating study and worth further explanation. Keep in mind for context sake that it was Cyrus who conquered Babylon and allowed the Jewish people to return to Jerusalem and build the temple. Because he conquered Babylon he was rightly called “king of Babylon”. As king of Babylon Cyrus had the authority to set the Jewish captives free as well as return the temple treasure taken by Nebuchadnezzar.In the book of Ezra the next Persian king who we see involved in the affairs of the Jewish people in the province of Babylon is Darius I.

-

- Now therefore, if it seem good to the king, let there be search made in the king’s treasure house, which is there at Babylon, whether it be so, that a decree was made of Cyrus the king to build this house of God at Jerusalem, and let the king send his pleasure to us concerning this matter.When Darius the king [of Babylon] made a decree, and search was made in the house of the rolls, where the treasures were laid up in Babylon. Ezra 5:17 – 6:1

Darius as the king of Babylon confirmed the decree of Cyrus and allowed the construction of the temple to continue. Darius also added his own monetary blessing to the effort. It’s interesting to note as Gerard Gertoux does in the quote below that the kingdom of Babylon became a Persian province (from the official Persian perspective) only after the death of Darius. It’s further worth noting that after a Babylonian revolt during the reign of Xerxes (son of Darius) that Xerxes never again used the title king of Babylon. In fact this official titulature became exceedingly rare during the reigns of the following Persian kings. In the appendices of this article I’ve included an interesting discussion of the only known occurrences of the title “king of Bayblon” used in conjunction with an unidentified “Artaxerxes”. As the authors note, there is no way to determine the identity of the Artaxerxes king of Babylon mentioned in these inscriptions.

-

- The former kingdom of Babylon became a Persian province only after Darius’ death and it is worthwhile noting that during his reign, Babylon was a satrapy of two big provinces (Babylonia and [lands] Beyond the River) and its ruler has been called “Governor of Babylon and Beyond the River24”. Thus the governor of the land of Judea was under the authority of Tattannu, the governor of [the lands] Beyond the River, exactly as the Bible reports:The copy of the letter which Tattenai the governor of the province Beyond the River and Shethar-bozenai and his associates the governors who were in the province Beyond the River sent to Darius the king (Ezr 5:6).

According to the Bible, Rehum ruled (538?-522) the province Beyond the River as “royal prefect” (Ezr 4:7-21), before Tattenai. (Queen Esther Wife of Xexes: Chronological, Historical and Archaeological Evidence – , Gerard Gertoux)

Here is the point. “King of Babylon” was a title rightly used by both Cyrus and Darius as Babylon was still a powerful kingdom with some autonomy granted during their reigns. By the latter half of Xerxes reign, Babylon was demoted (so to speak) and over the intervening years it lost more and more of its prestige and relevance. This brings us to a statement in Nehemiah 13:6 were it tells us that Nehemiah left Jerusalem in the 32nd year of “Artaxerxes king of Babylon”.

6 But in all this time was not I at Jerusalem: for in the two and thirtieth year of Artaxerxes king of Babylon came I unto the king, and after certain days obtained I leave of the king: (Nehemiah 13:6)

As I’ve tried to explain in these articles, Ezra describes king Darius as a Persian “Artaxerxes”. Because Ezra and Nehemiah were contemporaries this means that Nehemiah’s “Artaxerxes” was none other than Darius I ‘The Great’. Thus it makes much more sense here to see Nehemiah identify Darius as “Artaxerxes king of Babylon” than it does to try and apply that titulature to the Persian king Artaxerxes I (Longimanus) long after the kingdom of Babylon had been subsumed into the Persian empire. Both chronologically and historically, the title “king of Babylon” would have been more contextually appropriate to Darius I ‘The Great’ than his grandson Artaxerxes I (Longimanus).

-

- “Xerxes, designated by Darius as his successor, ascended the throne of Persia after twelve years as viceroy at Babylon. One of his first tasks was to suppress the revolt in Egypt begun in the lifetime of his father. This he did with great severity, forcing the Egyptian people to nurse their hatred in secret while awaiting their revenge. He acted with the same brutality towards Babylon, where revolt had also broken out: he razed the walls and fortifications of the city, destroyed its temple and melted down the golden statue of the god Bel. After this he ceased to use the title of ‘king of babylon’, calling himself simply ‘king of the Persians and the Medes’. (R. Girshman, Iran – 1951 p.190-191)

- Babylon Loses its Independence

“Babylon lost its independent status when it was merged with Assyria (Herodotus 7.63). After the fifth year of Xerxes’ reign the title “king of Babylon” was rarely used.” (Persia and the Bible – Edwin M. Yamauchi, 1994, p. 194) - Please note a further discussion of the title “King of Babylon” as used during the reign of Xerxes and Artaxerxes I as an appendices at the bottom of this post. (Waerzeggers, Caroline, and Maarja Seire. “Xerxes and Babylonia: the Cuneiform Evidence.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 277 (2018): n. pag. Print.)

- King of Assyria

Ezra 6:22 identifies Darius I ‘The Great’ as the “king of Assyria”. This is another instance where a Biblical author is using a title, in this case “king of Assyria” to emphasize a symbolic point relating to the history of the Jewish people. Remember it was Assyria who took Israel (the 10 tribes) captive. But now, long after Assyria ceased to be an official kingdom, a Persian “king of Assyria” is given credit for helping the Jewish return and build Yahweh’s holy temple. Yes, Yahweh had punished His people, but they had borne their punishment and outlasted their adversaries. In any case, Darius as “king of Assyria” is attested by Darius’ own Behistun inscription.

-

- And kept the feast of unleavened bread seven days with joy: for YHWH had made them joyful, and turned the heart of the king of Assyria unto them, to strengthen their hands in the work of the house of God, the God of Israel. (Ezra 6:22)

- [i.6]King Darius says: These are the countries which are subject unto me, and by the grace of Ahuramazda I became king of them: Persia, Elam, Babylonia, Assyria, Arabia, Egypt, the countries by the Sea, Lydia, the Greeks, Media, Armenia, Cappadocia, Parthia, Drangiana, Aria, Chorasmia, Bactria, Sogdia, Gandara, Scythia, Sattagydia, Arachosia and Maka; twenty-three lands in all. (emphasis mine)

- King of Kings

It’s worth noting here, that nearly all Achaemenid Royal inscriptions after Darius I attest to the Persian king titulature, “the great king, king of kings, the king of Persia” but it was Darius I who immortalized this tradition on the cliffs of Behistun and whom his sons and grandsons tried to emulated.

-

- 11 Now this is the copy of the letter that the king Artaxerxes gave unto Ezra the priest, the scribe, even a scribe of the words of the commandments of YHWH, and of his statutes to Israel. 12 Artaxerxes, king of kings, unto Ezra the priest, a scribe of the law of the God of heaven, perfect peace, and at such a time. (Ezra 7:11-12)

- Line 1 of Darius’ Behistun Inscription

I am Darius [Dâryavuš], the great king, king of kings, the king of Persia [Pârsa], the king of countries, the son of Hystaspes, the grandson of Arsames, the Achaemenid.

In Closing

I hope these articles have shown that the Bible consistently demonstrates its historical reliability if we accurately identify the context of its chronology. By separating Darius I from his Biblical title of “Artaxerxes”, scholars have unwittingly shifted Biblical history by nearly six decades from its original context and thus obscured some of the Bible’s most important history as it relates to secular Persian record.

As we’ll explore in forthcoming articles in this series, this shift of Bible history by nearly 60 years has really skewed our view of the 2nd temple era and this is no where better demonstrated than the history of the Biblical heroine Esther and her king.

Did you know that the Persian records attest to a man named Mordecai who was a high official in Persia during the 2nd temple era? One of the reasons you’ve probably never heard about this Mordecai is because he was a Persian official during the reign of Darius I.

Here is a fact. The name Mordecai is extremely rare in the Persian record. The name is also extremely rare in the Biblical record. In fact, an individual named Mordecai is only mentioned in the book of Esther as the uncle of Esther and in the books of Ezra & Nehemiah as one of the leaders of the people who came up with Joshua and Zerubbabel when Cyrus allowed the Jewish people to return to Jerusalem.

Curious, isn’t it, that two of the three records (historical and Biblical), where Mordecai is mentioned, place him as a leader in the early years of the 2nd temple era. Further, as I will do my best to demonstrate, the book of Esther by its own internal chronology also places the Biblical hero Mordecai in the early years of the 2nd temple era. This line of exploration will provide reasonable evidence to show that the Mordecai of the Persian records, the Mordecai of Ezra and Nehemiah, and the Mordecai of the book of Esther are one and the same person.

The result of this inquiry I hope is a further strengthening of your faith in the reliability of the Bible as an accurate account of history, with the bigger goal in mind of demonstrating that all Biblical history has an essential place in Yahweh’s redemptive plan for mankind through Yeshua.

I hope you’ll stay tuned. I think you’ll be thrilled at just how congruent the Bible is as it relates to us the history of the 2nd temple era.

Maranatha!

Next Time

Yahweh Willing my next article Mordecai & The Chronological Context of Esther will look at the chronological relationship between Mordecai, Esther, Darius, and their Biblical and secular contemporaries.

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_PLUS]

Post Script

The ‘Edayin Assumption

As mentioned above Mr. Lanser has updated his original article The Seraiah Assumption with some further thoughts and explanations in response to my rebuttal of his article as well as an email exchange we’ve had in the interim.

I can’t stress enough the importance the chronology of Ezra 4-6 has to providing us with the foundational context as it relates to the Bible’s identity of Darius as a Persian “Artaxerxes”. Further, Ezra 4:23-24 and the Bible’s use of the word ‘edayin’ is at the crux of whether Mr. Lanser’s objections to the use of the Artaxerxes as a title are valid.

Here is the bottom line. If the Bible uses the term “Artaxerxes” to describe Persian kings before this word was used as a throne name to describe the Persian king Artaxerxes I (Longimanus), then the entire pretext for a thematic (think non-chronological) view of Ezra 4-6 becomes untenable. In other words, if Artaxerxes was used in the Bible to describe Persian kings before Longimanus then the chronological premise of Mr. Lanser’s Seraiah Assumption is erroneous. I should add, it is not just Mr. Lanser’s interpretations that are affected by the Edayin Assumption, but every scholar who claims that the Artaxerxes of Ezra and Nehemiah is a reference to Artaxerxes I (Longimanus).

So let’s look at Mr. Lanser’s further explanation regarding the use of ‘edayin to see the Biblical merits of his case. I quote Mr. Lanser from his addendum titled: The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping Up Some Loose Ends Quotes from his article The Seraiah Assumption: Wrappin up Some Loose Ends are in green and where he quoted me in this article I’ve further highlighted them in brown for clarity.

The Meaning of ’Edayin

One of Mr. Struse’s most recent posts, “Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4” (https://www.the13thenumeration.com/Blog13/2019/05/04/cyrus-to-darius-the-2nd-temple-context-of-ezra-4/), spends considerable time discussing his understanding of the Hebrew term ’edayin and its exegetical significance. He claims that in every single case where the Aramaic word ’edayin is used, it carries a chronological/temporal significance:

But verse 23 presents a problem for Mr. Lanser’s interpretation. The Aramaic word ‘edayin’ is used 57 times in the Old Testament. 56 of those occurrences, including the “now” of Ezra 4:23, clearly refer to successive events which take place in chronological order. In most cases the events described by the word ‘edayin’ transpire directly after previously described events of the text. The only other occurrence of the world ‘edayin’ found in the Bible is Ezra 4:24 and is represented by the English word “then”.

If we use a consistent Hermeneutics we must translate ‘edayin’ in Ezra 4:24 in the same manner we translated it in verse 23 – as well as the other 55 other occurrences of the word found in the Old Testament. There is simply no other reasonable way to see ‘edayin’ other than a chronological synchronism which connects successive events. By placing ‘edayin’ at the beginning of both verse 23 & verse 24 the author of Ezra wanted to ensure there was no confusion about the chronological order of events.

My response was to “be a Berean” and check his information. I went to the online copy of Strong’s at http://www.blbclassic.org/lang/lexicon/lexicon.cfm?Strongs=H116&t=NASB and looked up the Aramaic term ‘edayin (אֱדַיִן). Near the beginning of that entry it notes, “i.q. Heb. אָז,” meaning it was the same as the Hebrew word אָז (‘az). I then checked my copy of the Enhanced Brown-Driver-Briggs Lexicon to look up that word. I found that EBDB on page 23 observes the word does not always have a strictly temporal significance; point 2 on that page shows it is also used for expressing logical sequence, i.e., “since A, then B.” Then I went to the Biblical Aramaic appendix to EBDB and checked the entry for ʼedayin. It referred me in turn to Gleason Archer’s standard reference book, the Theological Wordbook of the Old Testament (TWOT). Entry 2558 in that work states that the Aramaic term generally takes a temporal sense as Struse insists, but with one exception: “Used also with prepositions bĕ [בּ] or min meaning ‘since.’” If we go to the Aramaic text of Ezra 4:24, what do we find? The word used there is בֵּאדַיִן—ʼedayin with the preposition bĕ prefixed to it! This indicates logical sequence is intended, not temporal sequence. Ezra 4:23 does not include the prefix, so in that case a temporal meaning applies. The meanings are not identical.

The “then” of Ezra 4:24 therefore must be understood, based on rules of grammar, not as an action following consecutively in time after Ezra 4:23, but as completing the thought paused after Ezra 4:5, when the author, following a thematic rather than chronological contextual approach, went on a sidetrack about similar Samaritan problems which would take place in the future. Mr. Struse was honest in reporting that his source treats the ʼedayin of Ezra 4:24 differently from its other instances, but refused to accept this because he regards it as an unreasonable, purely subjective opinion. It is not, it is grammar-based, and I think the grammar rules should carry the argument. Mr. Struse’s statement, “There is simply no other reasonable way to see ‘edayin’ other than a chronological synchronism which connects successive events,” does not match up with the objective grammar-based evidence.

Mr. Lanser’s explanation above is disconcerting for several different reasons. First of all Mr. Lanser (as he’s done in his article regarding the Darius Assumption) misunderstands and then misstates my position. This erroneous basis he then uses as part of his understanding of the word ‘edayin. I’ll try to untangle the confusion this causes. I quote Mr. Lanser above:

“The “then” of Ezra 4:24 therefore must be understood, based on rules of grammar, not as an action following consecutively in time after Ezra 4:23, but as completing the thought paused after Ezra 4:5, when the author, following a thematic rather than chronological contextual approach, went on a sidetrack about similar Samaritan problems which would take place in the future. Mr. Struse was honest in reporting that his source treats the ʼedayin of Ezra 4:24 differently from its other instances, but refused to accept this because he regards it as an unreasonable, purely subjective opinion.”

If you carefully read Mr. Lanser’s quote of my article above (in brown), you’ll see that in fact I do not claim that my source treats “the ‘edayin of Ezra 4:24 differently from its other instances”. What I did say was that since Ezra 4:23 and the other 55 occurrences use ‘edayin in the same manner that we are obligated, by proper Hermeneutical method, to treat the occurrence of ‘edayin in verse 24 in the same manner as it is used in every other instance.

Mr. Lanser then compounded the error of his misunderstanding of my position (that ‘edayin was used exceptionally in verse 24) by not verifying for himself if this assumption about my position was in fact Biblically accurate. Even if I had made such a statement, if Mr. Lanser would have checked the use of the word ‘edayin he would have found such as statement to be totally erroneous.

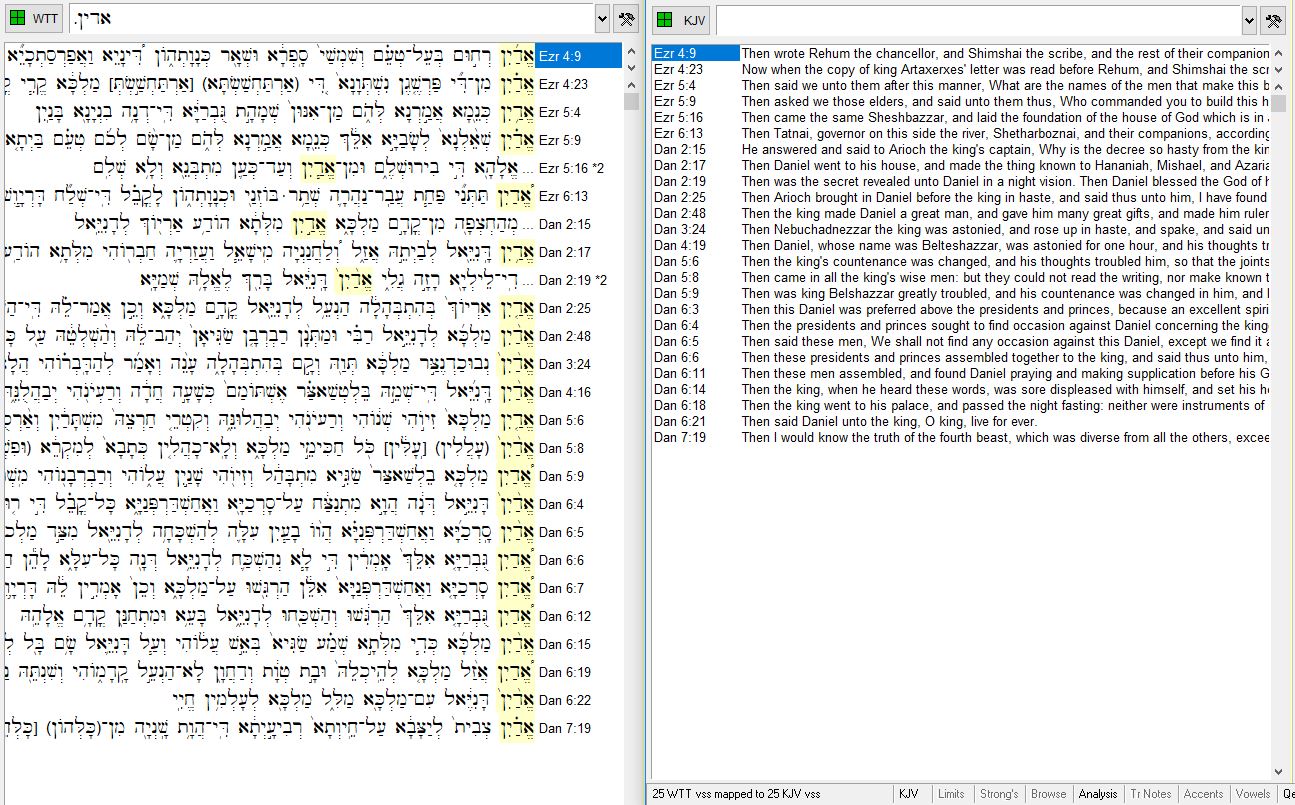

In the Bible ‘edayin with the prepositions bĕ [בּ] is not used exceptionally at all. In fact roughly half of the times ‘edayin is used, it has the preposition bĕ proceeding it. The following images show every occurrence of the word ‘edayin in the Bible. The first image shows ‘edayin without its preposition and the second image with its preposition bĕ. As you can see the usage of ‘edayin with or without its preposition bĕ, is roughly an even split. (you can click on image to enlarge)

Unfortunately for Mr. Lanser’s argument, he didn’t verify for himself how the prefix bĕ was used with ‘edayin in its other occurrences in the Bible. Had he done so, he would have realized that in each and every case in which ‘edayin with the preposition bĕ is used, it clearly describe a natural and chronological succession of events. For instance here is an occurrence of ‘edayin with the preposition bĕ where it is used to described events that took place after Yahweh’s divine command to restore and build Jerusalem. After Yahweh’s command the people “then” (‘edayin) they immediately obeyed His command by restarting construction on Yahweh’s house. Notice this occurrence of ‘edayin directly follows the same use of ‘edayin as given in Ezra 4:24 – the very “exception” Mr. Lanser uses to make his erroneous point.

23Now [אֱדַיִן] when the copy of king Artaxerxes’ letter was read before Rehum, and Shimshai the scribe, and their companions, they went up in haste to Jerusalem unto the Jews, and made them to cease by force and power.

24Then [בֵּאדַיִן] ceased the work of the house of God which is at Jerusalem. So it ceased unto the second year of the reign of Darius king of Persia. (Ezra 4:23 – 24)

1Then the prophets, Haggai the prophet, and Zechariah the son of Iddo, prophesied unto the Jews that were in Judah and Jerusalem in the name of the God of Israel, even unto them.

2 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] rose up Zerubbabel the son of Shealtiel, and Jeshua the son of Jozadak, and began to build the house of God which is at Jerusalem: and with them were the prophets of God helping them. (Ezra 5:1-2)

You’ve got to appreciate the irony here. These verses are the crux of Ezra’s 2nd temple era chronology as it relates to Yahweh’s divine command (word-dabar) to restore and build Jerusalem. The very command that I’ve demonstrated at this blog and in my book Daniel’s 70 Weeks: The Keystone of Bible Prophecy is the “word” (dabar) of Daniel 9:25. Right here where Mr. Lanser and many of his peers by necessity must see a “a thematic rather than chronological contextual approach” to Biblical history we have a very strong likelihood that the Bible confirms its own internal chronology by dating this period to a historical figure found in the Persian records at the start of Darius I’s reign.

In my opinion, the above use of ‘edayin clearly demonstrates that Ezra 4:23-24 must be seen as a straight forward and strictly chronological account that demonstrates the book of Ezra understood that at least two Persian kings where known by the title of “Artaxerxes” over a half a century before that title was chosen by Darius I’s grandson, Longimanus as a throne name.

Finally, for those you who would like a play by play example of how ‘edayin is used outside the book of Ezra – along with and without its prepositional prefix bĕ, here is a clearly chronological account from the book of Daniel where I’ve added the use of ‘edayin in brackets for clarity.

Daniel 6:10-22

10 Now when Daniel knew that the writing was signed, he went into his house; and his windows being open in his chamber toward Jerusalem, he kneeled upon his knees three times a day, and prayed, and gave thanks before his God, as he did aforetime.

11 Then [אֱדַיִן] these men assembled, and found Daniel praying and making supplication before his God.

12 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] they came near, and spake before the king concerning the king’s decree; Hast thou not signed a decree, that every man that shall ask a petition of any God or man within thirty days, save of thee, O king, shall be cast into the den of lions? The king answered and said, The thing is true, according to the law of the Medes and Persians, which altereth not.

13 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] answered they and said before the king, That Daniel, which is of the children of the captivity of Judah, regardeth not thee, O king, nor the decree that thou hast signed, but maketh his petition three times a day.

14 Then [אֱדַיִן] the king, when he heard these words, was sore displeased with himself, and set his heart on Daniel to deliver him: and he laboured till the going down of the sun to deliver him.

15 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] these men assembled unto the king, and said unto the king, Know, O king, that the law of the Medes and Persians is, That no decree nor statute which the king establisheth may be changed.

16 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] the king commanded, and they brought Daniel, and cast him into the den of lions. Now the king spake and said unto Daniel, Thy God whom thou servest continually, he will deliver thee.

17 And a stone was brought, and laid upon the mouth of the den; and the king sealed it with his own signet, and with the signet of his lords; that the purpose might not be changed concerning Daniel.

18 Then [אֱדַיִן] the king went to his palace, and passed the night fasting: neither were instruments of musick brought before him: and his sleep went from him.

19 Then [בֵּאדַיִן] the king arose very early in the morning, and went in haste unto the den of lions.

20 And when he came to the den, he cried with a lamentable voice unto Daniel: and the king spake and said to Daniel, O Daniel, servant of the living God, is thy God, whom thou servest continually, able to deliver thee from the lions?

21 Then [אֱדַיִן] said Daniel unto the king, O king, live for ever.

22 My God hath sent his angel, and hath shut the lions’ mouths, that they have not hurt me: forasmuch as before him innocency was found in me; and also before thee, O king, have I done no hurt.

Articles related to this series:

The Seraiah Assumption by Rick Lanser of Associates for Biblical Research

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping up Loose Ends by Rick Lanser

My response to Rick Lanser’s – The Seraiah Assumption:

Introduction – The Associates for Biblical Research Responds to the Artaxerxes Assumption

Part I – Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4

Part II – Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem

Part III – Darius the great Persian Artaxerxes: A Contextual Look at the Book of Ezra in the Light of Persian History

Part IV – Darius and the Kingdom of Arta

Part V – Darius, Artaxerxes, & the Bible: Confirming Royal Persian Titulature

Part VI – Mordecai & the Chronological Context of Esther

Part VII – Esther, Ahasuerus, & Artaxerxes: Who was the Persian King of 127 Provinces?

Part VIII – Darius I: A Gentile King at the Crux of Jewish Messianic History

Part IX – The Priests & Levites of Nehemiah 10 & 12: Exploring the Papponymy Assumption

Appendices:

Addition information on the use of “King of Babylon” as it applies to the Persian record:

(Waerzeggers, Caroline, and Maarja Seire. “Xerxes and Babylonia: the Cuneiform Evidence.” Orientalia Lovaniensia Analecta 277 (2018): n. pag. Print

(INTRODUCTION: DEBATING XERXES’ RULE IN BABYLONIA

Caroline Waerzeggers

(Leiden University)*

How did the debate about Xerxes’ Babylonian policy develop? The ortho-doxy, most clearly expressed by Cameron (1941) and de Liagre Böhl (1962), held that Xerxes punished Babylon severely after the uprisings of Šamaš-erība and Bēl-šimânni, by taking away the statue of Marduk from its sanctuary, by preventing further celebration of the Akitu (or new year) festival, by destroying the city, by eliminating the element ‘King of Babylon’ from his official titula-ture, and by splitting the satrapy of Babylon-and-across-the-River into two smaller units.5

Other renderings, for instance by Hansjörg Schmid (1981, 132– 135; 1995, 78–87), added details of Babylon’s supposed destruction, such as the diversion of the Euphrates and the demolition of its ziggurat. Furthermore, the Daiva inscription was used as evidence of Xerxes’ supposed policy of intolerance,6 and the dwindling amounts of Babylonian clay tablets in his reign were presented as proof of decline after his violent suppression of the revolts.7

In 1987, Amélie Kuhrt and Susan Sherwin-White argued that Böhl’s account “was based on a careless reading of Herodotus combined with incomplete Babylonian evidence and an implicit wish to make very disparate types of material harmonize with a presumed “knowledge” of Xerxes’ actions, policies, and character.

The supporters of the earlier orthodoxy had misinterpreted several clues: the passage in Herodotus about Xerxes’ removal of a statue from the temple of Babylon concerns the statue of a man rather than of Marduk; by Xerxes’ time the Akitu festival had long been suspended so that Xerxes could not have been responsible for any change of program; the shortening of his titulature happened gradually, not abruptly; and the element ‘King of Babylon’ continued to be used occasionally even into the reign of Artaxerxes I. 9

Xerxes or their aftermath: the Kedor-Laomer texts, for instance, have been explained as a literary reaction to repression in the later Persian period (Foster 2005, 369). A memory of a Babylonian uprising against Xerxes is preserved in Ctesias (Tuplin 1997, 397; Lenfant 2004, 124; Kuhrt 2014, 167) and echoes may be contained in Herodotus’ account of Xerxes’ sacrileges in Babylon (1.183; Tolini 2011, 447 ‘echo déformé’) and in the Zopyros episode (Rollinger 1998, 347–348; but see Rollinger 2003, 257). Otherwise, Greek accounts are either oblivious of the revolts or they preserve garbled recollections at best;

see Kuhrt 2010 and 2014.

5Böhl 1962, 111 and 113.

6Sancisi-Weerdenburg 1980, 1–47.

7Joannès 1989a, 126; van Driel 1992, 40; Dandamaev 1993, 42.

8 The quote is from Kuhrt 2014, 166 where she reflects on the 1987 article with SherwinWhite.

9 See Kuhrt and Sherwin-White 1987.

-

- The Ancient Near Eastern Chronology ForumTory

Re: Artaxerxes, king of Babylon

Sat Jun 11, 2011 03:31

198.78.98That may or may not be conclusive but Dandamayev knows these families and their archives like the back of his hand. So when he says in 1995(?), eleven years after the Kessler text was published, that the title “King of Persia, Media, King of Babylon and Lands” (LUGAL Par-su Ma-da-a-a LUGAL E.KI u KUR.KUR) is not attested at all for Artaxerxes the First, his word is good enough for me until someone proves him wrong.I think we might be missing the real mark here. Even if Artaxerxes I did use the above title, and the Kessler text from Uruk dates to his reign, the original question was did any Achaemenid ruler after Darius I and Xerxes I ever use the royal title “King of Babylon” immediately after their nomen. In Nehemiah 13:6 we have “Artaxerxes, King of Babylon.” In the Kessler text “King of Babylon” comes after “King of Persia, Media” not after the nomen Artaxerxes. It’s no trivial point. The Nehemiah text is exactly what Darius I and Xerxes I did (what Babylonian scribes did) with the title “King of Babylon” in Babylonian documents. It was affixed to the nomen as if to say it was the king’s primary title. That does not happen again until the Year 4 Artaxerxes tablet OECT X 191 from Hursagkalama and the other tablet from this location but with year-date broken away (OECT X 229).

- The Ancient Near Eastern Chronology ForumTory

I notice Rollinger is not absolutely certain these documents or the Kessler text dates to Artaxerxes I. He simply says that if they do there would be a remarkable continuity in the use of the “Babylon” element in the Achaemenid royal titulary after Xerxes. I am inclined to believe, at least for the moment, and possibly being misled in this by Dandamayev, that these three tablets all date to the reign of Artaxerxes II, perhaps in this relative order:

Artaxerxes II year 4 “King of Babylon, King of Lands” (OECT X 191)

Artaxerxes II year x “…Baby]lon and Lands” (OECT X 229)

Artaxerxes II year 24 “King of Persia, Media, Babylon, and Lands” (Kessler)

In Year 4 (401) Artaxerxes II defeated his brother Cyrus on the battlefield in Babylonia (Cunaxa). Hence “King of Babylon, King of Lands.” Towards the middle of the reign Babylonian scribes shifted back to putting the main Persian title “King of Persia” or “King of Lands” immediately after the nomen.

I have been privileged to learn a lot from your work and it has helped me understand in great detail

something that seemed confusing at best. Thanks

Most welcome, Veronica.

Good evening!

Congratulations on your good and holy work! My deepest thanks.

According to your chronological table, who was the Darius killed in the time of Alexander?

Thanks.

David.