Authors Note:

I hope you’ve all had a wonderful and productive summer. I’ve missed sharing these articles with you the past few months. July-September is our family’s busiest time of year. Besides my regular day job as a plumbing contractor, Winnie & I manage our local farmers market as well as tend our nearly two acres of orchards and gardens. Now that harvest season has peaked, hopefully I’ll be able to write more consistently. I have a few more articles to write responding to Associates for Biblical Research’s criticism of my writings on the 2nd temple era before I change subjects and look at some other rather challenging subjects that have been on my mind for a while.. Yahweh willing here are some of the subjects I will be exploring with you in the coming months.

Esther’s Ahasuerus

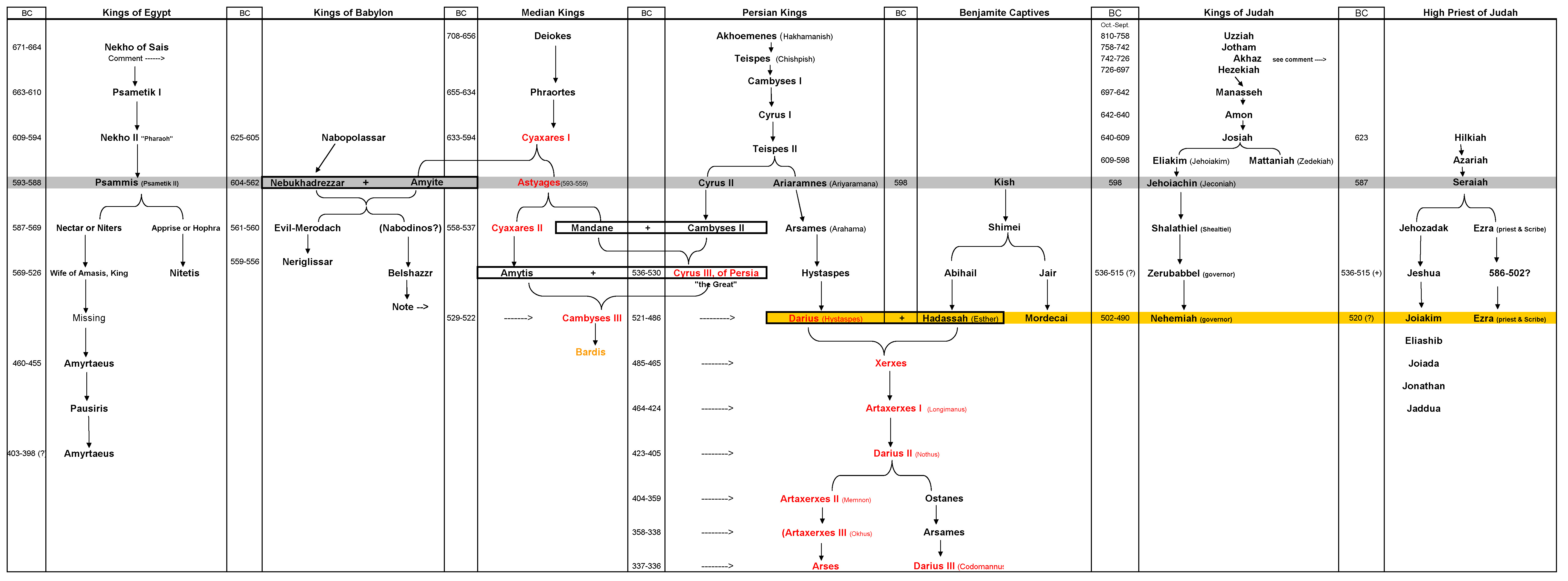

In this series of articles responding to Rick Lanser’s challenges and criticisms of my chronological view of the 2nd temple era (as posted on the Associate for Biblical Research website here) I’ve done my best to present what I believe to be an accurate and contextual view of the 2nd temple era. In that effort I’ve followed the chronology of the Bible from the decree of Cyrus in 536 BC (which allowed the Jewish people to return and build Jerusalem) up to the 7th year of “Artaxerxes” and Ezra’s departure for Jerusalem to teach the Jewish people the Torah.

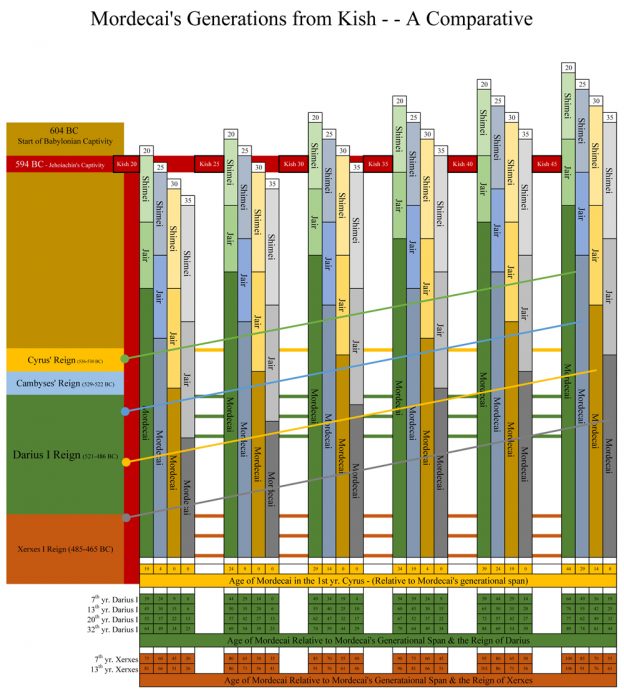

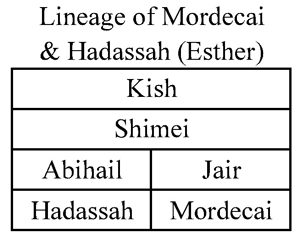

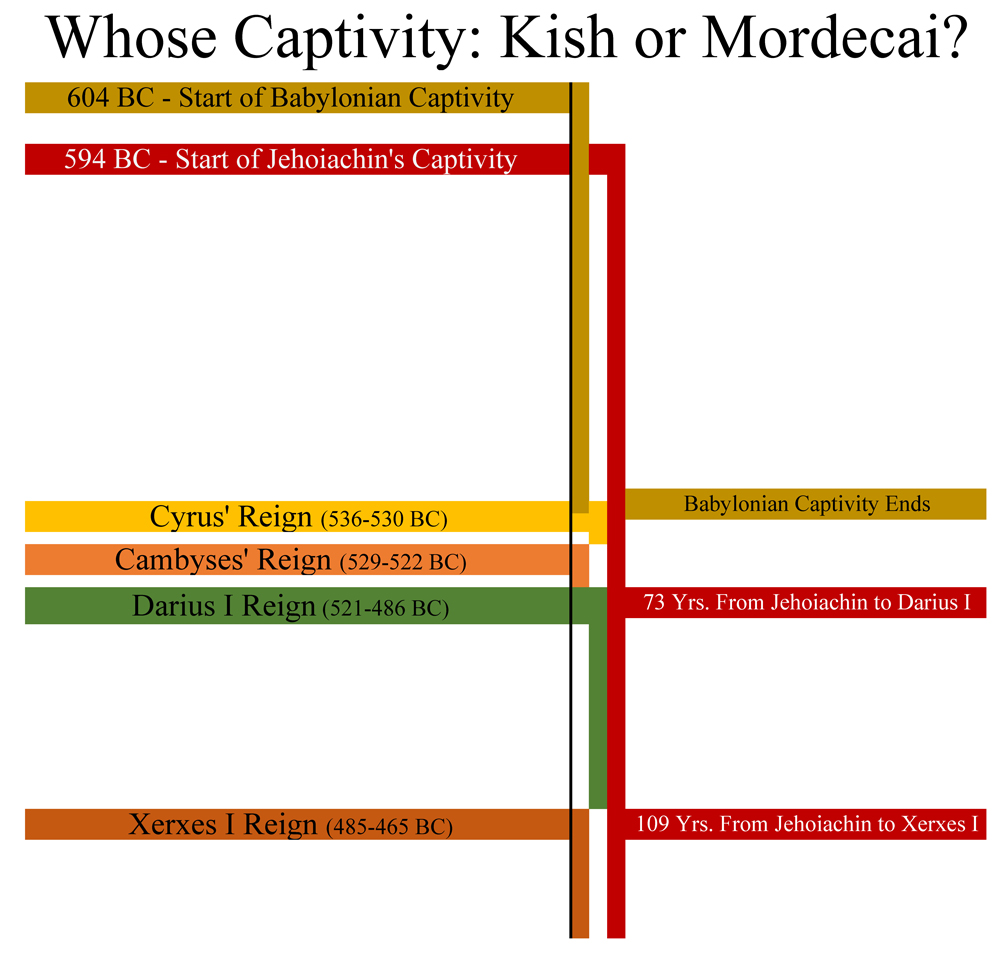

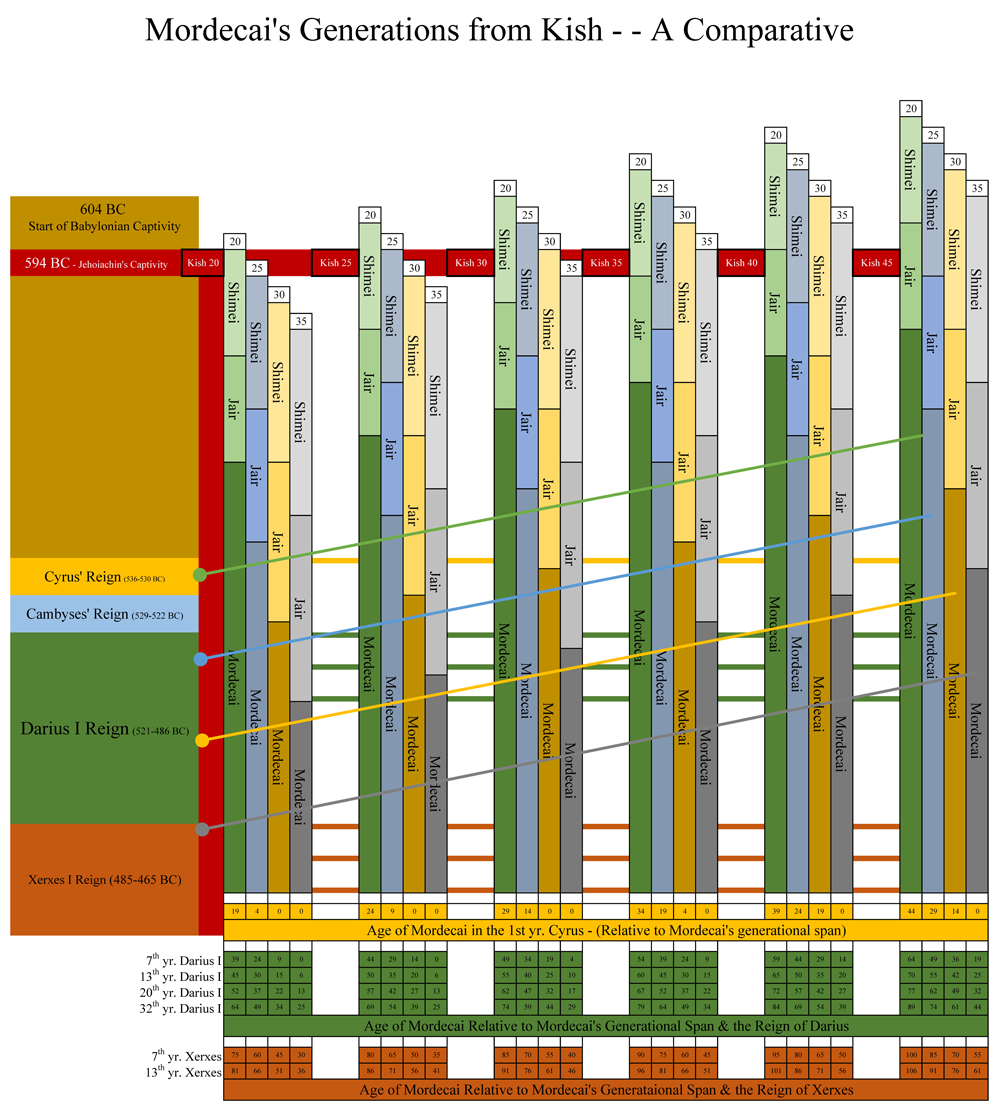

We’ve learned along the way that the Bible can be read in a straight forward and chronological manner as it relates to the Persian era. Indeed we’ve found that trusting the Bible in its most natural and common sense chronological reading provides the clearest and most natural way of understanding the chronology of the 2nd temple era. My last post (here) provided a reasonable Biblical and historical basis for believing that, at least chronologically, Esther’s uncle Mordecai could have been a contemporary of Darius I ‘The Great’. This Darius whom we know from the book of Ezra was also identified by the title “Artaxerxes” several decades before the term was first used by Artaxerxes I (Longimanus) as a throne name.

Granted this evidence did not conclusively prove that Darius and Mordecai were contemporaries or that “Ahasuerus” of the book of Esther is a reference to the Persian king Darius, but it did provide valuable chronological context to consider the likelihood of such an association.

King of 127 Providence

Now let’s further develop the Biblical evidence to see if there is any reason to further consider the possibility that the Persian king whom the Bible identifies as Darius might in fact be the Ahasuerus of the book of Esther. To do this let’s look at a couple of passages in the book of Esther that help identify this Persian king.

Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:) 2 That in those days, when the king Ahasuerus sat on the throne of his kingdom, which was in Shushan the palace, 3 In the third year of his reign, he made a feast unto all his princes and his servants; the power of Persia and Media, the nobles and princes of the provinces, being before him: 4 When he shewed the riches of his glorious kingdom and the honour of his excellent majesty many days, even an hundred and fourscore days. (Esther 1:1)

The book of Esther opens in the Persian city of Shushan with the Persian “Ahasuerus” (in his third year) throwing a feast for “all his princes and his servants” as well as the “nobles and princes of the provinces”. Notice this Ahasuerus the text further identifies as the “Ahasuerus” who reigned from India even unto Ethiopia over 127 provinces. This fact is helpful in identifying this Ahasuerus in several ways.

First of all, the implication in this statement is that the extent of this Persian’s kingdom (127 provinces) was a fact known well enough to the readers of the book of Esther that it would help identity him. This identification also implies an extent to the kingdom of Persia that was not matched by other Persian kings, otherwise the identification with 127 providence would have had no relevance to the reader.

The Persian Empire of Artaxsaca

The Persian Empire of Artaxsaca

Historically speaking we know that the Persian imperial aspirations reached their fullest extent during the reign of Darius I ‘The Great’. In the following quote Richard Tyrwhitt explains why only Darius I qualifies as the Ahasuerus of 127 provinces mentioned in the Esther 1:

“The ‘great king’ of the book of Esther is distinguished – at least from his predecessors – as the king who ruled from India to Ethiopia. Of these opposite extremities of the Persian empire when it had reached its widest limits, we showed that the African Ethiopians were first conquered by Cambyses, while the Indian dependents were first acquired by Darius the father of Xerxes; whereupon we argued that, as two kings had reigned over this extent of nations before Artaxerxes, the fact of their subject condition could not with propriety be applied either by a contemporary or by a later writer to distinguish the reign of Artaxerxes.

In like manner we argue now against Xerxes. He could not with propriety be distinguished from the kings who had preceded him by the fact, that he reigned from Hindu to Kush, form the Upper Indus to the Upper Nile, because Darius his father had already possessed this empire. Our inference, therefore, is, that Xerxes is not the Ahasuerus of Esther.”

Claiming that the author of Esther, when distinguishing the Persian king Ahasuerus who ruled over 127 providence from his peers – was reference to Xerxes the son of Darius I – would be the equivalent of an historian today trying to distinguish the Presidency of John F Kennedy from his peers by claiming he was the President of all the 50 Untied States of America. Indeed there were 50 states when Kennedy became president but it was during the presidency of Dwight D. Eisenhower (Kennedy’s predecessor) that 49th and 50th state were added to the United States of America. Any honor for this distinction belongs to Eisenhower not Kennedy.

Likewise it was during the reign of Darius I ‘The Great’ that Persia reached its greatest territorial breath that included 127 provinces. Trying to apply this distinction to Xerxes, Darius’ son makes no historical sense and undermines the credibility of the Biblical record related to the Persian period.

The book of Esther confirms that Darius I is the most likely candidate for Esther’s king in another way as well. In Esther 9-10 it tells us that the Ahasuerus of Esther still had 127 provinces in his 13th year of reign. It further tells us that this was the Persian king who “laid a tribute upon the land, and upon the isles of the sea.” Historically speaking, this description of Esther’s Ahasuerus only truly fits the Persian king Darius I, because it was he who laid tribute upon the isle of the Mediterranean Sea.

And the king Ahasuerus laid a tribute upon the land, and upon the isles of the sea. (Esther 10:1)

I defer once again to Edmund Tyrwhitt in his book Esther and Ahasuerus: An Identification of the Persons so Named. He explains it this way:

“Darius was the Persian monarch who fixed the tributes of the subject nations. The other is equally important to our argument. He alone was lord of the Greek islands in the Aegean, after the twelfth year of his reign. No former king of Persia had been their lord, and though they formed part of the empire, which Darius bequeathed to his son Xerxes, they were lost to Xerxes after that destruction of his fleet at Mycale in the seventh year of his reign, which we have had occasion to relate. Of all the islands, Samos was the first conquered by Darius, if not also lost by Xerxes…..(Edmund Tyrwhitt, Esther and Ahasuerus: An Identification of the Persons so Named p.174)

Darius was a Huckster

Darius is to be distinguished from his peers as the Persian king who instituted a commodities based system of tribute which his subjects could, when necessary, use in lieu of gold and silver. This novel form of tribute earned the deprecation of “huckster” from Herodutus. Once again I quote Tyrwhitt:

“The principal change which the measures of Darius introduced into the king’s tributes, appears to have been a substitution of silver and gold for articles of local production. To make up the royalty due from each nation, there may have been established in consequence of this change, places of deposits in every satrapy, and periodical sales on account of the kings’ revenue, of corn, wine, oil, or whatever other local produce; and this may have given occasion for the sarcasm above noticed, that king Darius had become a “huckster,”…. (Edmund Tyrwhitt, Esther and Ahasuerus: An Identification of the Persons so Named p.175-176)

For confirmation of this new provincial form of tribute we have to look no further than the 2nd year of Darius I and his declaration which allowed the Jewish people to continue building the temple. Notice in the following quote the items that were considered “tribute”.

Let the work of this house of God alone; let the governor of the Jews and the elders of the Jews build this house of God in his place. 8 Moreover I make a decree what ye shall do to the elders of these Jews for the building of this house of God:

that of the king’s goods, even of the tribute beyond the river, forthwith expenses be given unto these men, that they be not hindered 9 And that which they have need of, both young bullocks, and rams, and lambs, for the burnt offerings of the God of heaven, wheat, salt, wine, and oil, according to the appointment of the priests which are at Jerusalem, let it be given them day by day without fail: (Emphasis mine – Ezra 6:7-9 )

Notice just a few years later in Ezra 7 this same king Darius (whom Ezra 6 identifies by the title “Artaxerxes”) once again offers items of tribute from his royal treasury in support of the Jewish peoples efforts to reestablish their temple worship.

Artaxerxes, king of kings, unto Ezra the priest, a scribe of the law of the God of heaven, perfect peace, and at such a time. 13 I make a decree, that all they of the people of Israel, and of his priests and Levites, in my realm, which are minded of their own freewill to go up to Jerusalem, go with thee.

14 Forasmuch as thou art sent of the king, and of his seven counsellors, to enquire concerning Judah and Jerusalem, according to the law of thy God which is in thine hand; 15 And to carry the silver and gold, which the king and his counsellors have freely offered unto the God of Israel, whose habitation is in Jerusalem, 16 And all the silver and gold that thou canst find in all the province of Babylon, with the freewill offering of the people, and of the priests, offering willingly for the house of their God which is in Jerusalem: 17 That thou mayest buy speedily with this money bullocks, rams, lambs, with their meat offerings and their drink offerings, and offer them upon the altar of the house of your God which is in Jerusalem. 18 And whatsoever shall seem good to thee, and to thy brethren, to do with the rest of the silver and the gold, that do after the will of your God. 19 The vessels also that are given thee for the service of the house of thy God, those deliver thou before the God of Jerusalem. 20 And whatsoever more shall be needful for the house of thy God, which thou shalt have occasion to bestow, bestow it out of the king’s treasure house.

21 And I, even I Artaxerxes the king, do make a decree to all the treasurers which are beyond the river, that whatsoever Ezra the priest, the scribe of the law of the God of heaven, shall require of you, it be done speedily, 22 Unto an hundred talents of silver, and to an hundred measures of wheat, and to an hundred baths of wine, and to an hundred baths of oil, and salt without prescribing how much. 23 Whatsoever is commanded by the God of heaven, let it be diligently done for the house of the God of heaven: for why should there be wrath against the realm of the king and his sons?

24 Also we certify you, that touching any of the priests and Levites, singers, porters, Nethinims, or ministers of this house of God, it shall not be lawful to impose toll, tribute, or custom, upon them. 25 And thou, Ezra, after the wisdom of thy God, that is in thine hand, set magistrates and judges, which may judge all the people that are beyond the river, all such as know the laws of thy God; and teach ye them that know them not. 26 And whosoever will not do the law of thy God, and the law of the king, let judgment be executed speedily upon him, whether it be unto death, or to banishment, or to confiscation of goods, or to imprisonment. (Ezra 7:12-26)

So you appreciate the congruency here, notice that not only did “Artaxerxes” (Darius I) in the passage above offer support for rebuilding the Jewish people’s religious sanctuary, but he also encouraged Ezra to teach the Jewish people the laws of their God.

Darius went even further though. He gave Ezra the authority to establish a legal system which was based in the Torah (law of Moses). That this was in fact the modus operandi of Darius I is confirmed in multiple examples from Babylon to Egypt. A good example comes from Egypt in the 3rd year of Darius (519 BC) about the same time as Darius was offering support to the Jewish peoples in their efforts to reestablish temple worship, he was also helping the Egyptians codify their laws.

Like his efforts related to the Jewish temple worship, Darius efforts on behalf of the Egyptians were not just limited to the codification of their laws. There also are multiple examples of Darius’ efforts to rebuild their places of worship. I quote once again from Pierre Briant’s book From Cyrus to Alexander:

Darius and the Egyptian Laws

I was just about the same date, 519, that Darius sent a letter to his satrap in Egypt, which we know (in fragmentary form) from a text on the back of the Demotic Chronicle. Darius ordered his satrap to assemble Egyptian sages, chosen from among priests, warriors, and scribes. They were instructed to gather in writing all of the old laws of Egypt down to year 44 of Pharoah Amasis, that is, 526 – the eve of the Achaemenid conquest. The commission worked for sixteen years (519-503) and produced two copies of its work, one in Demotic, the other in Aramaic.

The text does not detail the exact content of the book that they produced. It simply distinguishes “public (or constitutional) law,” temple law”, and “private law.”

The Seven Wise Men of Artaxerxes

The Seven Wise Men of Artaxerxes

Another place that potentially links the Bible’s Darius I (a.k.a. Artaxerxes) of Ezra 6 & 7 with Ahasuerus of Esther is found in the so called Persian “Seven”.

When Darius came to power in Persia he was assisted by 6 other Persians in his conspiracy to remove the usurper Bardyia. These men, while not equal with the king, were considered his councilors and had some influence and power with regard to the affairs of the Persian empire. This is important because we find a similar 7 councilors advising both the Darius of Ezra 6 and the Ahasuerus of Esther. Pierre Briant explains the significance:

Darius and the Six

Primus inter pares?

We must now return at greater length to the relations between Darius and his companions after his accession to the throne. Reading Herodotus without perspective, on actually receives the impression that Darius was bound by the agreements that had been mutually reached by the Six when he came to power (Otanes having taken himself out of the competition), concession that basically would have made the new king primus inter pares. According to Justin (who had read his Herodotus carefully), as a result of the murder of the magus, “the Great ones (principles) were equal in merit and nobility (virtute et nobilitate….pares; I.10.1-2) This is the version also found in Plato (Laws 695c) in an otherwise very suspicious passage: “When [Darius] came and seized the empire with the aid of the other six, he split it up into seven divisions, of which some faint outlines still survive today.”…..

Diodorus as late as the fourth century specifies that the satrap Rhosaces “ was a descendant of one of the seven Persians who deposed the Magi (XVI.47.2), Quintus Curtius introduces Orsines, chieftain of the tribe of Pasargade, who was “a descendant of the ‘seven Persians’ and tracing his genealogy also to Cyrus” (IV.12.8) The permanence of the term thus seems assured. But does this mean that the Seven constituted an entity that had the ability to control the activities of the king?

…This interpretation is also based on Ezra and Esther, where Ahasuerus is shown convening “the seven administrators of Persia and Media who had privileged access to the royal presence and occupied the leading positions in the kingdom” (Esher 1:13-14)( Preirre Briant, From Cyrus to Alexander p.128-129 excerpted)

12 Artaxerxes, king of kings, unto Ezra the priest, a scribe of the law of the God of heaven, perfect peace, and at such a time. 13 I make a decree, that all they of the people of Israel, and of his priests and Levites, in my realm, which are minded of their own freewill to go up to Jerusalem, go with thee. 14 Forasmuch as thou art sent of the king, and of his seven counsellors, to enquire concerning Judah and Jerusalem, according to the law of thy God which is in thine hand; (Ezra 7:12-14)

Then the king said to the wise men, which knew the times, (for so was the king’s manner toward all that knew law and judgment: 14 And the next unto him was Carshena, Shethar, Admatha, Tarshish, Meres, Marsena, and Memucan, the seven princes of Persia and Media, which saw the king’s face, and which sat the first in the kingdom;) 15 What shall we do unto the queen Vashti according to law, because she hath not performed the commandment of the king Ahasuerus by the chamberlains? (Esther 1:13-1)

There is nothing simple about looking into the past and trying to understand history from the point of view of those who wrote it. But if we take the pieces of evidence we find in the Bible related to Ezra’s Darius “even” Artaxerxes and compare it with the evidence we find in the book of Esther, it is evident that Darius I best fits the Biblical template of the king who rule over 127 provinces from India to Cush and who laid tribute upon the isles of the sea.

Further as we’ve seen above there is a great deal of additional chronological and historical evidence that suggest that Darius I whom the book of Ezra describes as an “Artaxerxes” (before the throne name was taken by his grandson) was also the king the book of Esther describes as “Ahasuerus”.

Answering More Objections from ABR’s Rick Lanser

Now that I’ve provided you with some fascinating  historical and Biblical context related to Darius, Ahasuerus, and Artaxerxes, I would like to further strengthen the context of this information by addressing some of Mr. Lanser’s objections to my associations between Esther’s Ahasuerus and the Darius “even” Artaxerxes of Ezra 6 & 7. If you are just joining this discussion here are the prior articles in this series as well as the original links to Mr. Lanser’s articles posted on the Associate for Biblical Research website.

historical and Biblical context related to Darius, Ahasuerus, and Artaxerxes, I would like to further strengthen the context of this information by addressing some of Mr. Lanser’s objections to my associations between Esther’s Ahasuerus and the Darius “even” Artaxerxes of Ezra 6 & 7. If you are just joining this discussion here are the prior articles in this series as well as the original links to Mr. Lanser’s articles posted on the Associate for Biblical Research website.

Articles related to this series:

The Seraiah Assumption by Rick Lanser of Associates for Biblical Research

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping up Loose Ends by Rick Lanser

My response to Rick Lanser’s – The Seraiah Assumption:

Introduction – The Associates for Biblical Research Responds to the Artaxerxes Assumption

Part I – Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4

Part II – Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem

Part III – Darius the great Persian Artaxerxes: A Contextual Look at the Book of Ezra in the Light of Persian History

Part IV – Darius and the Kingdom of Arta

Part V – Darius, Artaxerxes, & the Bible: Confirming Royal Persian Titulature

Part VI – Mordecai & the Chronological Context of Esther

Part VII – Esther, Ahasuerus, & Artaxerxes: Who was the Persian King of 127 Provinces?

Part VIII – Darius I: A Gentile King at the Crux of Jewish Messianic History

Part IX – The Priests & Levites of Nehemiah 10 & 12: Exploring the Papponymy Assumption

For clarity’s sake, as I go through these quotes from Mr. Lanser article The Seraiah Assumption (in brown) I will add my own comments in black with further quotations by others in green. I quote Mr. Lanser:

The Ahasuerus of Esther (ch. 1:1; etc.) is generally identified with the king whom the Greeks called Xerxes. The Hebrew Achashwerosh is a much closer transliteration of the Persian Khshayârshâ or the Babylonian from Achshiyarshu than is the Greek Xerxes. It should not be forgotten that the vowels did not come into the Hebrew Bible manuscripts until about the 7th century AD. Hence, the Hebrew author of Esther reproduced only the consonants of Khshayârshâ and wrote ’Chshwrwsh…The spelling of the name Ahasuerus in Ezra 4:6 is the same as in Esther, and linguistically fits, of all known Persian kings, only the name of Xerxes.

Philip Brown II, in “The Chronological Relation of Ezra and Nehemiah,” Bibliotheca Sacra 162 (Apr–Jun 2005) (https://bible.org/seriespage/chapter-2-temporal-ordering-ezra-part-ii), whose excellent work we will look further at below, adds:

Contrary to older commentators’ frequent citation of the “well-known fact” that Persian kings had multiple names, no extant archeological or inscriptional evidence equates Cambyses with Ahasuerus or Artaxerxes with Pseudo-Smerdis, or uses Artaxerxes as a general title for Persian monarchs. From a philological standpoint, H. H. Schaeder’s analysis of vwrwvja and vsvjtra establishes beyond reasonable doubt that Ahasuerus and Artachshashta are in fact the Aramaic names for Xerxes and Artaxerxes (emphasis added).

I think it’s only fair to point out here that the absence of evidence is not in inself any form of evidence. Historically speaking the Persians kept a verbal tradition but left very little in the way of a written literary tradition. In fact, in some ways the Bible provides us with more literary information about the kingdom of Persia than the known Persian records themselves. I find it difficult to understand the tendency of Biblical scholars to automatically discount the chronological details given in the Bible when those details to not agree with the current meager evidence of secular history.

Pierre Briant, one of the most respect Persian scholars of our era had this to say about the literary tradition of the Persians:

“The Persians, however, left no literary record of their own history. The only form of official historiography in this period is the genealogies recorded by the kings themselves.”

Need I say more?

I return to Mr. Lanser’s thoughts – picking up where we left off in the quote above:

Thus, we must conclude that Ahasuerus was a personal name that was modified by passing through different languages. Ahasuerus was neither a throne name nor a title.

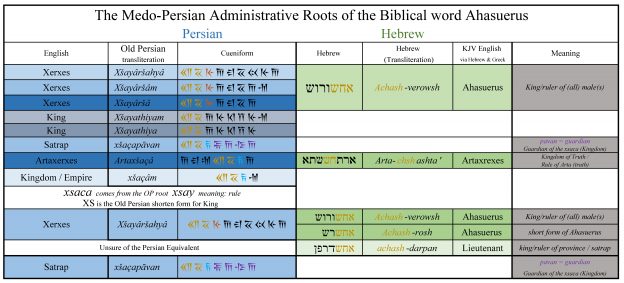

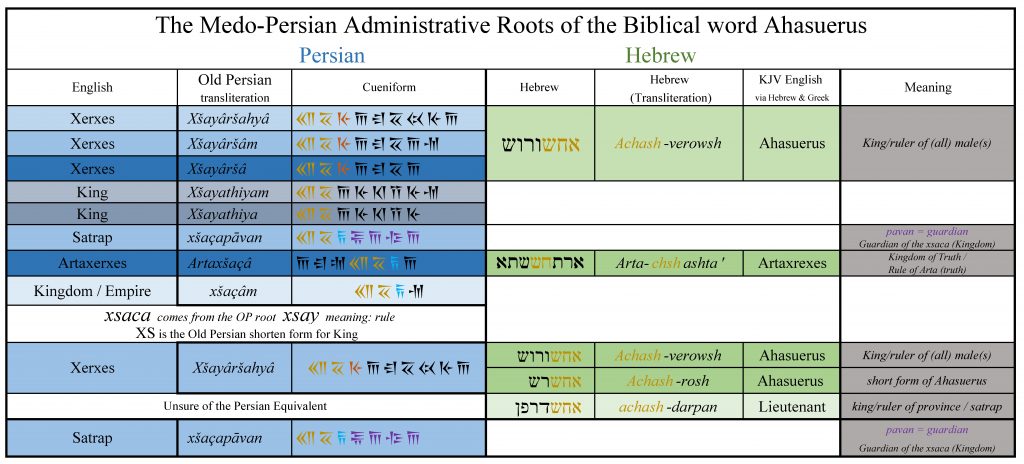

Was Ahasuerus a peronsal name? Let’s start by offering some clarifications regarding the name Ahasuerus and Xerxes. First of all, the Old Persian Xšayārša / Xšayāršam / Xšayâršahyâ (Greek =Xerxes) by some accounts pronounced Khshayârshâ is an Old Persian compound word), the meaning of which is xšay ‘king/rule’ + aršan ‘male’ thus literally the word means ‘king/ruler of (all) male (men, etc) Further the word xšay (rule) is of Median origins and the root of the Old Persian word for “king” (i.e. Xšayathiya / Xšayathiyam).

Old Persian Lexicon

For further study here is a link to an Old Persian Lexicon: https://archive.org/details/OldPersian

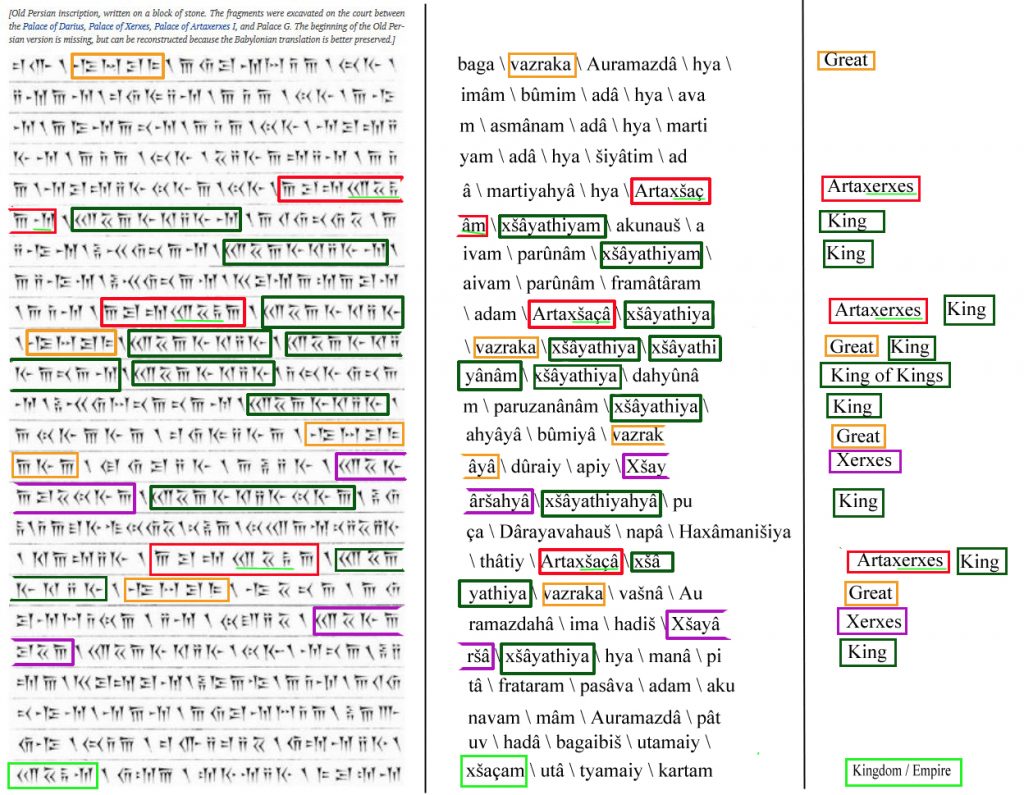

For those interested in confirming spelling and transliteration of these words from the original cuneiform script, below I’ve provided a translation of the Aechamenid Royal inscription A1Pa courtesy of Livius.org. In that inscription, which I’ve color coded, you’ll find the cuneiform and phonetic spelling of the words king, Xerxes, Artaxerxes, and Kingdom as well as their English translation.

Interestingly, I’ve also learned in researching this, that many scholars believe that Persian administrative words such as Vazrak “great”, xšāyaθya-“king”, xšassa-“kingdom” had Median origins. Concerning the Median origins of Persian administrative vocabulary Walter Bruno Henning, the highly respected German scholar of Persian languages and literature had this to say:

“As is well known, the administrative vocabulary of Old Persian was largely borrowed from Median”.

So at least tentatively we might conclude that the Persian throne name we know from Greek history as Xerxes (OP = Xšayâršahyâ) has Median etymological roots and that in its most literal and natural rendering could well have been used to describe Median and Persian males who rule.

Was Ahasuerus a Personal Name

But what about Mr. Lanser’s claim that the Biblical rendering of Xerxes name as Ahasuerus or more accurately as he claims without vowel pointings as “Chshwrwsh” must not be considered a title or a throne name but rather it “was a personal name that was modified by passing through different languages.”?

First of all, this statement doesn’t really make sense in light of the fact the Mr. Lanser believes that the Biblical “Ahasuerus” is more accurately given as “Chshwrwsh” and that this word is a close transliteration of the Persian Xšayâršahyâ pronounced Khshayârsha and by the Greeks loosely as Xerxes. I quote Mr. Lanser:

The Hebrew Achashwerosh is a much closer transliteration of the Persian Khshayârshâ or the Babylonian from Achshiyarshu than is the Greek Xerxes.

Later in his article Mr. Lanser further emphasizes his point with:

But despite the seemingly solid identification of Ahasuerus with Xerxes,…

The problem shared by both of these suggestions is that they ignore a patently obvious fact: all through the book of Esther we encounter the name “Ahasuerus” where it refers to Xerxes. (Excerpted for clarity – full quote below)

So if as we’ve seen in this article, Ahasuerus, (Xšayâršahyâ) given in its Hebrew spelling as Chshwrwsh comes from the Median root xsay (rule) and literally means a king or ruler of all males (men), it is hard to see how this evidence demands that we “must conclude” that Ahasuerus is a personal name.

This claim by Mr. Lanser is further undermined by Daniel 9 of all places.

The Father of Darius the Mede

To help us further understand how the Bible used the word “Ahasuerus” we turn to Daniel chapter 9. This, the greatest prophetic chapter of the Bible opens with a chronological synchronism which provides us with a fixing point for when the prophecy was given to Daniel.

In the first year of Darius the son of Ahasuerus, of the seed of the Medes, which was made king over the realm of the Chaldeans; (Daniel 9:1)

Also I in the first year of Darius the Mede, even I, stood to confirm and to strengthen him. (Daniel 11:1)

Keep in mind that “Darius the Mede” was believed to be the leader of Cyrus’ army that fateful night Babylon fell (some historians even believe this is a reference to Cyrus himself). Regardless of the identity of this Darius the Mede, it is important to observe that Daniel identifies Darius, the Mede’s father as an Ahasuerus long before the same name was given to Esther’s king. This further weakens the argument that this Ahasuerus was a personal name.

What’s really neat here though is that without the knowledge that some Persian administrative words had Median origins, some might be inclined to believe that the Bible got it wrong by claiming that both a Median and a Persian were known by Ahasuerus. But as explained above this is not the case because, the Bible’s Ahasuerus was the rending of the Old Persian word Xšayâršahyâ which means male ruler/king and this word Xšayâršahyâ finds it’s etymological roots in the Median root word xšay (rule) hence it was a Median loan word connected to administration of Medo-Persian affairs.

To emphasize the Median origins of Persian administrative vocabulary I again quote Walter Bruno Henning, the highly respected German scholar of Persian languages and literature:

“As is well known, the administrative vocabulary of Old Persian was largely borrowed from Median”.

Kings and Lieutenants

But let’s look at this from another angle and test Mr. Henning’s statement with a comparison of two Persian “administrative” words found in the Bible. We know now with reasonable confidence that the Hebrew word transliterated Achashverowsh (un-pointed Chshwrwsh) – further transliterated via the Greek Septuagint as Ahasuerus in our English Bibles – is the Hebrew transliteration of Old Persian Xšayâršahyâ (Greek=Xerxes). A bit complicate, no? Stick with me here, because this is pretty neat stuff.

We also learned that the Old Persian word Xšayâršahyâ better known to you and I as Achashverowsh/Ahasuerus/Xerxes has as its root the Median administrative word xšay which means “to rule” or “ruler”.

Now take a look at Xšayâršahyâ as it is represented in Hebrew. The highlighted red Hebrew letters Alef, Cheit, Shin, אחשורוש (the Chsh sound) would be the Hebrew transliteration of the Old Persian xšay or “ruler”. The letters Vav, Reish, Vav, Shin, then would represent the Hebrew equivalent of the Persian âršahy which means male, men, mankind etc. (Please understand this is a way oversimplification of the linguistic nuances of the subject)

That we are likely on the right track regarding our tentative understanding of meaning of the OP Xšayâršahyâ and the Hebrew Achashverowsh can be confirmed with the Hebrew word אחשﬢרפן (achashdarpan) which our English Bibles translate as Lieutenants or Princes.

To help you understand the context of this word I’ve provided three different places this word is used in our Bible. As you read these verses, notice I’ve arranged them roughly chronologically. My first example of achashdarpan comes from the reign of Darius the Mede, the second from 7th year of Darius (a.k.a. Artaxerxes) and the third comes from the book of Esther and the time of the Persian Ahasuerus.

It pleased Darius [Darius the Mede son of Ahasuerus] to set over the kingdom an hundred and twenty princes, which should be over the whole kingdom; (Daniel 6:1)

And they delivered the king’s commissions unto the king’s lieutenants, and to the governors on this side the river: and they furthered the people, and the house of God. (Ezra 8:36)

And all the rulers of the provinces, and the lieutenants, and the deputies, and officers of the king, helped the Jews; because the fear of Mordecai fell upon them. (Esther 9:3)

As you can see from its usage above achashdarpan (princes/lieutenant) is indeed a Median-Persian administrative word. In most of our Hebrew Bible lexicons they give the meaning of the word as a satrap or governor of a Persian province. Taking the Hebrew word אחשﬢרפן (achash-darpan) apart then we see it has as its root the same אחש (achash) which comes from the Median root word xšay for “ruler”. The second half of the Hebrew achashdarpan ﬢרפן(darpan) likely then is Hebrew equivalent of the Old Persian pavan which we translate today as satrap.

So putting achash-darpan together we get an approximate meaning of “ruler/king of the satrap/province”. The following chart provides a more visual comparison of these words in their various Persian and Hebrew forms.

From 120 to 127 Provinces

As a side note here, notice that chronologically there were 120 provinces set up by Darius the Mede when he became the “king of Babylon” under Cyrus the Persian. By the time of Esther’s king the Persian empire had grown to 127 provinces. Again it is worth repeating that the Persian Xsaca (empire) reached its fullest measure during the reign of Darius I ‘The Great’. By the 7th year of his son Xerxes that empire started to shrink. Esther 9:30-32 tells us that by the 13th year of Esther’s “Ahasuerus” there were still 127 provinces. Further Esther 10:1 opens with the statement that this same Ahasuerus laid tribute upon the “land and the isles of the sea”, a historical description which most accurately describes Darius I ‘The great’ and a description which by the 7th year of his son Xerxes would no longer have accurately applied.

It pleased Darius [Darius the Mede son of Ahasuerus] to set over the kingdom an hundred and twenty princes, which should be over the whole kingdom; (Daniel 6:1)

Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:) (Esther 1:1)

Ahasuerus was an Administrative Title

The evidence we’ve developed here further strengthens the case that we’ve been building that the Biblical usage of Achashverowsh/Ahasuerus/Xerxes was not a Biblical personal name. Rather this word was the Hebrew transliteration of a Medo-Persian administrative title which meant “king/ruler of men”.

As such it usage first in a Median context as a title for the father of “Darius the Mede” (Dan. 11), then subsequently as a title for the Persian king Cambyses (Ezra 4:6), and finally as a title for Esther’s Persian king (Est. 1:1) provides not only an accurate, but chronological and congruent usage of the word that only a contemporary of that era would have known.

The sum of all this I believe, provides compelling evidence the word Xšayâršahyâ /Achashverowsh/Ahasuerus was first used in the Bible as a general title to identify three different Persian rulers before it was later chosen as a throne name by Darius I’s son Xerxes. And further that this usage of the word in the Bible in no way eliminates Darius I ‘The Great” as a contender for the Biblical identity of Esther’s king Ahasuerus.

Artaxerxes and its Median Roots

Before moving on, take one more look at the chart above and you’ll see that not only does Ahasuerus (Xšayâršahyâ) and King ( Xšayathiya) have roots in the Median administrative word xšay but so does the title or name we know as Artaxerxes (Artaxšaçâ). This just adds to the evidence that Artaxerxes, before it was a throne name chosen by Xerxes son Longimanus, may well have been used as part of the administrative vocabulary of the author of the book of Ezra to describe the Persian king Darius I.

Returning now to Mr. Lanser’s objections:

But despite the seemingly solid identification of Ahasuerus with Xerxes, doesn’t the context restrict itself to events between Cyrus and Darius? If we look at the list of Achaemenid rulers given near the beginning of this article, we see Xerxes did not rule until after Darius I. This break from chronological order tempts some to abandon plain-sense interpretation principles, and look instead for other ways to understand the passage. One is by overlooking or dismissing the etymology behind the name, instead suggesting “Ahasuerus” was not the personal name for Xerxes resulting after some translational gymnastics, but a title for some other king who lived between Cyrus and Darius, perhaps Cambyses or Smerdis. The problem shared by both of these suggestions is that they ignore a patently obvious fact: all through the book of Esther we encounter the name “Ahasuerus” where it refers to Xerxes. Shouldn’t the Ahasuerus in Ezra 4:6 likewise be Xerxes? To hold this view is simply recognizing that Scripture really has one Author, God, who we rightly expect to be self-consistent. Since He inspired the writers of Scripture, shouldn’t we be looking for a way to accommodate the plain-sense implication of this—that the Ahasuerus of Esther was also the Ahasuerus of Ezra 4:6—rather than arguing against it?

As I explained above, his reasoning here does not take into account the Biblical usage of the word Ahasuerus in referring to the Median “Ahasuerus” father of “Darius the Mede” (Dan. 6:1) Mr. Lanser’s explanation above also does not take into account the Median and Persian etymological roots of the word Ahasuerus found in the Medo-Persian word (xšay) which means king/ruler.

After posting his article The Seraiah Assumption on the Associates for Biblcial Research website, (which I have been quoting from above) Mr. Lanser and I had further email correspondence were I pointed out the error of his reasoning concerning the usage of Ahasuerus in the Bible. Mr. Lanser then updated his Seraiah Assumption article in an attempt to further clarify his position regarding Ahasuerus and several other topics. If you have not read Mr. Lanser’s updated thoughts I’d encourage you to read his entire article The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping Up Some Loose Ends so you have the complete context of his thoughts before you continue with my response to his updated thoughts.

I continue now with Mr. Lanser’s The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping Up Some Loose Ends:

Consistent with Wilson’s scholarship, I presented in my Seraiah Assumption article a chart where Dr. William Shea summarized the most recent ancient language studies. They indicate the name “Ahasuerus” in Ezra 4:6 was not a generic “title” for Persian kings, but a personal name. Shea showed how the original Old Persian form of the name mutated into Ahasuerus—the very name used throughout the book of Esther. I pointed this out in a private email to Mr. Struse, and he replied (5/30/2019, most typos as in the original):

Regarding William Shea’s ancient language studies I’m not sure why you believe that is some sort of conclusive proof. As I’m sure you know “Ahasuerus” is the Hebrew version of the Persian word Khshayarsha. The unpointed Hebrew word being “‘chshwrsh”. The Mesoretes [sic] added the vowel pointings which gave us “Ahasuerus”. In my opinion Esther 1:1 is sufficient evidence to prove that the Hebrew Ahasuerus is a title. The verse reads:

Esther 1:1 KJV Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces…)

The author of Esther opens with “in the days of Ahasuerus”. Then he goes on to clarify that this “Ahasuerus” was the “Ahasuerus” who ruled over 127 provinces from India to Ethiopia. If “Ahasuerus” was personal name of single king then the author of Esther would not have need to make the clarification that this Persian king was the one who rule over 127 Provinces. The only reasons to make such a distinction would be to make sure the reader understood which “Ahasuerus” was being mentioned.

The reasoning that this was a “single king whom the Greeks knew as Xerxes” further falls downs when we consider that in Greek history there were no other “Xerxes” before Xerxes son of Darius (Hystaspes). Yet the Bible clearly tells us that there was a Median king named “Ahasuerus” who was the father of Darius the Mede, the same Median who (under Cyrus) was made king of Babylon circa 538-536 BC. This was several generations before the Xerxes I of Greek fame. This also proves that Ahasuerus was at the very least, a title used by more than one Persian and most probably just a general title given to Persian kings, possibly to signify some connection to the Median side of the Medeo-Persian peoples.

Please note here that my email response above to Mr. Lanser was before I understood that in fact the Persian Ahasuerus has etymological roots in the Median administrative nomenclature. As noted in the email above I speculated that Ahasuerus had some connection to the Medo-Persian peoples but was not sure. As this article explores Ahasuerus does indeed have roots in the Median administrative word xšay which means “to rule” and by further implication “king”.

Although calling “Khshayarsha” a “word” rather than a “name” seems to be an attempt to blunt the force of the historical evidence by redefining it, Mr. Struse did make a valid factual point above. He is correct that the name “Ahasuerus” was also applied to another king; Daniel 9:1 informs us that an earlier “Ahasuerus,” usually identified with Astyages, was the father of Darius the Mede. However, this man was a predecessor of Cyrus the Great and had nothing to do with the Persian Achaemenid period, my focus, so I did not discuss him. I agree that, in view of the existence of this earlier Ahasuerus, it makes sense that Esther 1:1 could be taken as a statement clarifying which Ahasuerus was being discussed in Esther—the one who was the son of Darius the Great, not the earlier one who was the father of Darius the Mede. My point was that there was only a single king in the Achaemenid Period under discussion who went by the name Ahasuerus.

Unfortunately for Mr. Lanser’s readers in the above he gave no indication that he only had the Persian Aehaemenid period in mind when he made his statement about Ahasuerus. Here is Mr. Lanser’s original claim for context:

The problem shared by both of these suggestions is that they ignore a patently obvious fact: all through the book of Esther we encounter the name “Ahasuerus” where it refers to Xerxes. Shouldn’t the Ahasuerus in Ezra 4:6 likewise be Xerxes? To hold this view is simply recognizing that Scripture really has one Author, God, who we rightly expect to be self-consistent.

If indeed we are to recognize that the Scripture really has “one Author, God, who we rightly expect to be self-consistent”, then we must include the Medo-Persian usage of Ahasuerus into our interpretational matrix when trying to understand the usage of this word, especially in light of the fact that the word Ahasuerus find its roots in Median administrative nomenclature. Including the Median usage of Ahasuerus and its etymological roots into our matrix turns Mr. Lanser’s argument on its head and in fact leads to the opposite conclusion. Namely that the Biblical usage of Ahasuerus in the Bible was in fact a more general title based in Medo-Persian administrative nomenclature and not a personal name. Mr. Lanser continues:

Bringing up the fact that there was a Median king by that name prior to Cyrus should not obscure the fact that there is no evidence for any Persian “Ahasuerus” after Cyrus, save for that king whom the Greeks knew as Xerxes. To cite well-meaning but inadequately informed commentators of yesteryear as evidence Cambyses II held the “title” of “Ahasuerus” is to shut one’s eyes to contemporary historical evidence.

I think I’ve demonstrated that the “well-meaning but inadequately informed commentators of yesteryear” were closer to the truth than Mr. Lanser would like to believe. Mr. Lanser’s conclusions above do not take into account the etymological roots of the xšay from which is derived the Old Persian title Xšayâršahyâ /Achashverowsh/Ahasuerus. Mr. Lanser continues:

Moreover, if “Ahasuerus” was just a common “title” for Persian kings generally, what would be the point of mentioning it if the intent of Esther 1:1 was to clarify exactly which king was being discussed? It does not help to identify the exact king if “Ahasuerus” was simply a generic title. If instead it was a personal name or perhaps a throne name, though, it has real value in narrowing down the options.

This statement completely ignores that most natural reading of Esther 1:1 which indicates that Ahasuerus was indeed a general title which the text of Esther 1:1 clarified by adding that this “Ahasuerus” was the Ahasuerus of 127 provinces. If Ahasuerus was anything but a general title, the author would not have needed to qualify him as the king of 127 provinces. Mr. Lanser continues:

Thus, I believe it makes better sense to view “Ahasuerus” as either a throne name taken by two Medo-Persian kings or as an example of papponymic name repetition.

It is evident that Mr. Lanser’s opinion is evolving because his statement above contradicts his earlier conclusion from his original article The Seraiah Assumption. In his original article he claimed that “Ahasuerus” could not be title or a throne name. He provides no explanation for this change in position. I quote from Mr. Lanser’s original article The Seraiah Assumption (notice the emphasis Mr. Lanser provides in his original article):

Thus, we must conclude that Ahasuerus was a personal name that was modified by passing through different languages. Ahasuerus was neither a throne name nor a title.

Returning to Mr. Lanser’s – Wrapping up Loose Ends:

The further observation that the intended king [Esther’s Ahasuerus] was fabulously wealthy, because he inherited an expansive empire from his father Darius the Great—who is never called either Ahasuerus or Artaxerxes anywhere in any historical records—is used to narrow the options down to only one.

For reasons explained more fully in my responses above, the wealth, dominion, and tribute ascribed to Esther’s Ahasuerus could only rightly be attributed to Darius I ‘The Great’. As we’ve seen the chronological and historical details provided by Esther disqualifies Xerxes as the Ahasuerus of Esther.

Finally, I don’t know if Mr. Lanser meant to be somehow more specific in his statement above but his claim that “Darius the Great – who is never called either Ahasuerus or Artaxerxes anywhere in any historical records” is simply not accurate.

Just a few hundred years after the events in the book of Ezra and Esther were recorded, the Septuagint version of the Hebrew Scriptures was translated into Greek. In this translation of the Bible the authors identified the Hebrew Esther’s “Ahasuerus” by the title Artaxerxes.

(300-200 BC)

LXE Esther 1:1 In the second year of the reign of Artaxerxes the great king, on the first day of Nisan, Mardochaeus the son of Jairus, the son of Semeias, the son of Chisaeus, of the tribe of Benjamin, a Jew dwelling in the city Susa, a grat man, serving in the king’s palace, saw a vision.

This association between Ahasuerus, Artaxerxes, and Darius is further confirmed by the Greek Ester as well as the apocryphal book of 1 & 4 Esdras.

KJA Ester (Greek) 11:2 In the second year of the reign of Artexerxes the great, in the first day of the month Nisan, Mardocheus the son of Jairus, the son of Semei, the son of Cisai, of the tribe of Benjamin, had a dream;

KJA 4 Esdras 1:1 The second book of the prophet Esdras, the son of Saraias, the son of Azarias, the son of Helchias, the son of Sadamias, the sou of Sadoc, the son of Achitob, 2 The son of Achias, the son of Phinees, the son of Heli, the son of Amarias, the son of Aziei, the son of Marimoth, the son of And he spake unto the of Borith, the son of Abisei, the son of Phinees, the son of Eleazar, 3 The son of Aaron, of the tribe of Levi; which was captive in the land of the Medes, in the reign of Artexerxes king of the Persians.

Ester (Greek) 16:1 The great king Artexerxes unto the princes and governors of an hundred and seven and twenty provinces from India unto Ethiopia, and unto all our faithful subjects, greeting.

KJA 1 Esdras 3:1 Now when Darius reigned, he made a great feast unto all his subjects, and unto all his household, and unto all the princes of Media and Persia, 2 And to all the governors and captains and lieutenants that were under him, from India unto Ethiopia, of an hundred twenty and seven provinces.

KJV Esther 1:1 Now it came to pass in the days of Ahasuerus, (this is Ahasuerus which reigned, from India even unto Ethiopia, over an hundred and seven and twenty provinces:)

Even if you don’t believe that the books of Esdras and the Greek Ester were “inspired” at the very least they represent a version of history understood by the authors of their day.

As testified by the Septuagint, the translators understood the Xšayâršahyâ /Achashverowsh/Ahasuerus of the Hebrew Bible to be synonymous with the title Artaxerxes. This usage of Artaxerxes in place of Esther’s Ahasuerus only makes sense if these titles were seen by the Hebrew authors as being interchangeable administrative titles for Persian kings – before – these titles were enshrined as Persian throne names.

Further if 1 Esdras (written in 100 BC/AD?) understood Darius to be the king of 127 provinces, this underscores the fact that early on in Biblical tradition Darius = Ahasuerus = Artaxerxes.

Finally I leave you with a few more historical quotes from the time of Yeshua up until the 17th century which show that some historians did in fact believe that Darius was also known by the titles Artaxerxes or Ahasuerus.

Josephus – a contemporary of Yeshua

Now, in the first year of the king’s reign, Darius feasted those who were about him, and those born in his house, with the rulers of the Medes, and princes of the Persians, and the toparches of India and Ethiopia, and the generals of the armies, of his hundred and twenty-seven provinces (Antiquities of the Jews 11:33, emphasis mine)

Rashi – 1000 AD

and Artaxerxes:

He is Darius, but he was called Artaxerxes because of the province and the kingdom, for all kings of Persia were thus named just as all the kings of Egypt were called Pharaoh (Solomon ben Isaac (Rashi) circ. 1000 AD.

Ussher – 1600’s

Mordecai, the Jew, in the Greek edition of Esther {Apc Est 11:1-12}, is said to have had a dream on the first day of the month of Nisan, in the second year of the reign of Artaxerxes the Great (or Ahasuerus or Darius, the son of Hystaspes), concerning a river signifying Esther and two dragons portending himself and Haman. 3484c AM, 4194 JP, 520 BC (Ussher, Annals of the World, p. 126 , section 1015, emphasis mine)

Next Time

Due to the length of time between these articles on Darius, Ahasuerus, and Artaxerxes and the volume of information covered, Yahweh willing next time I’ll summarize the evidence and make some conclusions relating to Darius, Ahasuerus, and Artaxerxes.

Hopefully after that in a final article in this series we will look at the chronology from Ezra 7 and the 7th year of Darius “even” Artaxerxes up to the final years of Nehemiah’s governorship. In this article we will look at the fascinating and complex details off the priests and Levites who came up with Joshua and Zerubbabel and their relationship to the priests and Levites in the days of Nehemiah.

Until then Maranatha!

Articles related to this series:

The Seraiah Assumption by Rick Lanser of Associates for Biblical Research

The Seraiah Assumption: Wrapping up Loose Ends by Rick Lanser

My response to Rick Lanser’s – The Seraiah Assumption:

Introduction – The Associates for Biblical Research Responds to the Artaxerxes Assumption

Part I – Cyrus to Darius: The 2nd Temple Context of Ezra 4

Part II – Darius & Artaxerxes: The Context of the Word to Restore & Build Jerusalem

Part III – Darius the great Persian Artaxerxes: A Contextual Look at the Book of Ezra in the Light of Persian History

Part IV – Darius and the Kingdom of Arta

Part V – Darius, Artaxerxes, & the Bible: Confirming Royal Persian Titulature

Part VI – Mordecai & the Chronological Context of Esther

Part VII – Esther, Ahasuerus, & Artaxerxes: Who was the Persian King of 127 Provinces?

Part VIII – Darius I: A Gentile King at the Crux of Jewish Messianic History

Part IX – The Priests & Levites of Nehemiah 10 & 12: Exploring the Papponymy Assumption

[DISPLAY_ULTIMATE_PLUS]

A Favor to Ask.

If you are a regular reader of this blog, you know that you can download all of my books and articles free of charge. I don’t ask for donations or allow advertisements on this blog. This effort is a labor of love for me as a testimony to Yahweh’s wonderful redemptive plan for mankind through Yeshua. I don’t want your money but if you would take a moment to share the articles you read on this blog with your friends and family on Facebook, Twitter, and other social media I would greatly appreciate your help. Together we can share the Biblical evidence for Yahweh’s wonderful redemptive plan for mankind. Thank you for your help in this effort!

* * *

FREE Book Download:

If you would like to learn more about Biblical history and Bible prophecy, you might also appreciate my books in the Prophecies and Patterns series.

At the following link you may download one of the three books shown below. If you like the book and would like to download the other two, all I ask is that you subscribe to my blog. I won’t share your email or spam you with advertisements or other requests. Just every couple of weeks I’ll share with you my love of Biblical history and Bible Prophecy. Should you decide you no longer wish to be a subscriber you can unsubscribe at any time.

Click the following link to download your Free book: Book Download

I hope you’ll join the adventure!